The gastrocnemius (G. gaster, belly ; kneme, leg.), or “gastroc” for short, is the largest muscle in the calf, which acts on both the ankle and knee joints.

It shares the role of prime mover in ankle plantarflexion with the soleus, but only when the knee is straight. The gastroc becomes less active the more the knee joint is bent.

Classified as part superficial posterior compartment of the leg, the gastrocnemius lies superficial to the soleus and is responsible for the vast majority of the visual impact of the calf.

Note: The gastroc and soleus are collectively known as the “triceps surae,” meaning “three-headed muscle of the calf.” This is because they perform the same action and share the same insertion.

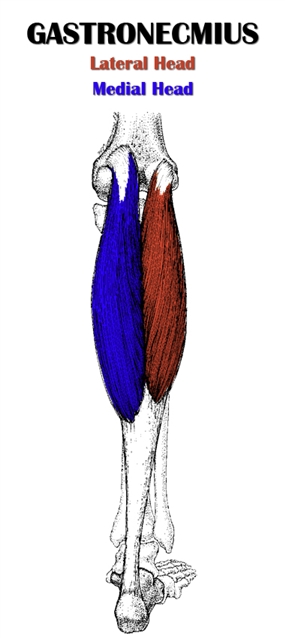

The gastrocnemius has two heads: the lateral head and the medial head, which is the longer of the two.

The lateral and medial heads originate from the lateral and medial sides (respectively) of the distal posterior femur. They insert on the Achilles tendon, which attaches to the heel bone.

The fibers of each head mirror each other as they travel obliquely toward the central tendon separating them, creating a bipennate fiber arrangement.

Table of Contents

Also Called

- Gastroc

- Calf

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Lateral Head | Medial Head |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Lateral surface of the lateral condyle of the femur | Popliteal surface of the femur, just superior to the medial condyle of the femur |

| Insertion | Posterior surface of the calcaneus via the Achilles tendon | Posterior surface of the calcaneus via the Achilles tendon |

| Action |

|

|

| Nerve Supply | Tibial nerve (S1-S2) | Tibial nerve (S1-S2) |

Exercises

Note: The chart below contains direct gastrocnemius exercises only. However, the gastroc is trained indirectly in hamstring exercises.

Barbell Exercises

- Standing calf raise

- Safety bar standing calf raise

Dumbbell Exercises

- Standing calf raise

Cable Exercises

- Standing calf raise (with hip harness attachment)

Machine Exercises

- 45° calf raise

- 45° calf press

- Standing calf raise

- Smith machine standing calf raise

- Seated straight-knee calf press

- Seated straight-knee calf extension

- Donkey calf raise

Sled Exercises

- 45° calf raise

- 45° calf press

- Seated straight-knee calf press

- Hack calf raise

- Lying calf raise

- Vertical calf press

Weighted Exercises

- Standing calf raise (with hip belt or dip belt)

- Donkey calf raise

- Donkey calf raise (with hip belt or dip belt)

Bodyweight Exercises

- Standing calf raise

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques

Stretches

- Floor board straight-knee calf stretch

- Lunging straight-knee calf stretch

- Pike straight-knee calf stretch

- Floor-seated straight-knee calf stretch (requires good hip and lower back flexibility)

- Floor-seated straight-knee calf stretch with towel

- Step straight-knee calf stretch

- Wall straight-knee calf raise

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

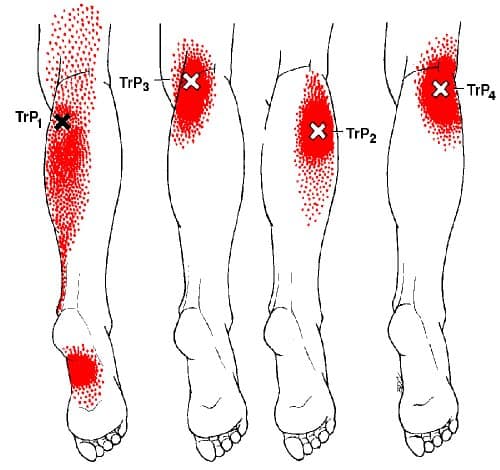

When using these techniques, give special attention to the common trigger points shown in the image below.

- Foam roller

- Lacrosse ball

- Sprinter Stick

Common Issues

- Overactive/Short Gastrocnemius: People with lower crossed syndrome (LCS) and/or pronation distortion syndrome (PDS) typically have overactive and short gastrocnemius. In LCS, the gastroc can become overactive/short as a result of poor hip extension during walking/running due to weak glutes and hamstrings; as such, it must compensate by becoming overactive during ankle plantarflexion and knee flexion to propel you forward. The ankle pronation, knee adduction and knee internal rotation associated with pronation distortion syndrome, weakens and lengthens the medial head of the gastrocnemius while causing the lateral head to shorten and become tighter. Overuse of the gastroc from excessive walking/running will also cause overactivity, and can lead to or worsen the above-mentioned postural distortions. An overactive/short gastroc inhibits ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, which in turn limits knee flexion range of motion during squats or similar movements – Specifically, it can cause compensation in the form of excessive hip flexion and/or lumbar flexion, and a tendency to lean forward and lift the heel off the floor when squatting. If not addressed, an overactive/short gastroc and any related postural and movement distortions may lead to strains/tears of the muscle or Achilles tendon, or pain in the foot (e.g. plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis), ankle, lower leg (e.g. shin splints), knee or lower back.

Training Notes

- If you have overactive/short gastroc, do the following:

- Cut down on the amount of time you spend running or walking, if possible.

- Do gastrocnemius stretch and release techniques throughout the day. Do the same for your soleus, since it will also be overactive/short.

- Since the plantarflexors (i.e. gastroc, soleus, etc.) are overactive/short, the dorsiflexors (i.e. the tibialis anterior and the various muscles on the front of the lower leg) are inhibited/lengthened. As such, you need to strengthen the dorsiflexors. Any reverse calf raise variation will do the trick.

- If you have pronation distortion syndrome, you’ll have to focus on releasing/stretching the lateral head of the gastroc. And if the medial head is weak, you’ll have to strengthen it by doing straight-knee calf raises with the hips and toes turned out. Then, among other things, you’ll need to release/stretch the hip adductors, hip flexors, IT band and fibularis muscles, while strengthening the glutes and hip external rotators. See how to fix pronation distortion syndrome (article coming soon).

- If you also have lower cross syndrome, you’ll have to deal with some underlying issues. This includes strengthening your glutes, abs and obliques, plus releasing/stretching your hip flexors and lower spinal erectors – to name a few things. See how to fix lower cross syndrome (article coming soon).

- If you want to build build bigger and stronger gastroc muscles, these guidelines and training tips will help:

- First, understand that the gastrocnemius consists predominantly of fast twitch muscle fibers. This means it generally responds best to high intensity, explosive training. Knowing this, we can devise an intelligent training strategy, such as the one described in the bullets below:

- Do 5 sets of 5 reps with heavy weight on any straight-knee calf exercise, twice per week.

- Don’t go so heavy that you lose range of motion.

- Use an explosive, but controlled tempo: 3 seconds down, hold a mild stretch at the bottom for 1 second, explode up as fast as possible, and squeeze at the top for a full second. Don’t bounce up from the bottom.

- For most people, rest between sets should be about 3 minutes. The goal is to rest until you feel fresh for the next set.

- To emphasize the medial head, externally rotate your hips to point your toes out. Pointing your toes in or straight ahead trains each head about evenly. There’s no stance that will train the lateral more than the medial head.

- While the gastroc is the most important muscle for calf aesthetics, you should not ignore soleus exercises if you want to full calf development. Also, see calf training for more calf workout information.

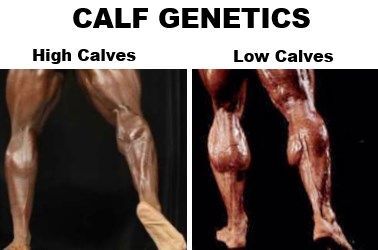

- The extent to which genetics play a role in the shape and size potential of the calves is arguably greater than in any other muscle group. That is, some people will have great calves with no training, while others will have relatively unimpressive calves despite years of consistent proper training. I’ll talk specifics, below:

- The length of the Achilles tendon affects the length of the gastroc, which has huge impact on overall calf aesthetics. A long Achilles tendon means that the gastroc is shorter and naturally smaller because it attaches to the tendon at a higher point on the calf (i.e. “high calves” or “high calf insertions”). Conversely, a short Achilles tendon equals a longer and naturally bigger gastroc due to the lower attachment point (i.e. “low calves” or “low calf insertions”).

Johnnie Jackson’s calves on the left, Dorian Yates’ calves on the right. - If you have high calf insertions, you’ll need to accept that you’ll never have large, great-looking calves. You should still train them, though, because they can still get bigger and look better. Just temper your expectations.

- On the bright side, though, people with long Achilles tendons/high calves tend to be faster and more athletic overall. However, this may not be a direct result of long Achilles. Rather, it’s more likely that long Achilles are correlated with other athletic traits.

- If you have low calf insertions, consider yourself lucky. You can get away with doing no direct calf exercises and you’ll still have large, shapely calves. If you decide to train them directly, then they’ll be god-tier.

- If you’re somewhere in between low and high calves, you can build some sizable and decent looking calves if you train them intelligently and consistently – though they probably won’t look as good as someone with very low insertions who never trains calves.

- The length of the Achilles tendon affects the length of the gastroc, which has huge impact on overall calf aesthetics. A long Achilles tendon means that the gastroc is shorter and naturally smaller because it attaches to the tendon at a higher point on the calf (i.e. “high calves” or “high calf insertions”). Conversely, a short Achilles tendon equals a longer and naturally bigger gastroc due to the lower attachment point (i.e. “low calves” or “low calf insertions”).

Related Muscles

- Soleus

- Plantaris

When will you post the articles dealing with UCS, LCS, and PDS?

It might be a while — did you have any specific questions I could answer for you now, though?

Is it possible to “over-strengthen” the tibialis anterior by not balancing it out with enough work for the gastrocnemius? I am trying to sort out an odd pain at the back of my knee/low lateral calf, and am wondering if it’s possible to overdo the reverse calf raises.

I haven’t heard of that being common, but that’s probably because most people don’t do much reverse calf work (or activities that overuse the tib ant). Still, if you did too much reverse calf raise work, I’m sure an imbalance could occur overtime. The best thing to do would be to ease into any changes when trying to fix imbalances. Don’t just add a bunch of reverse calf raise volume all at once. Increase it slowly, assess progress, then re-assess any changes. If pain continues or gets work, consult a physical therapist.