This guide will teach you how to select the best barbell for your home gym.

Not only will I include several of the best barbell recommendations on this page. I’ll also give you all the knowledge you need to analyze any given barbell. I’ll do this by explaining these important topics:

- Why you should care about buying a quality barbell

- The 3 main types of bars: Powerlifting barbells vs Olympic Weightlifting barbells vs Multipurpose/CrossFit barbells

- The anatomy of a barbell, meaning its different parts/components

- What the common barbell specs/features are, and what they mean

Table of Contents

Why You NEED a Quality Barbell & What It Will Cost

The #1 mistake people make when building their home gym is buying a low quality barbell. The #2 mistake is buying the wrong type of barbell for their training style.

Many people don’t realize that the barbell is actually the most important piece of equipment to invest in. Think about it. You use it on most of your exercises, including on all of the heaviest and most important ones. And it’s a piece of equipment that you’re in direct contact with throughout the entire lift. It’s the only thing between you and hundreds of pounds of weight.

You need something that gives you safety and performance. You definitely should NOT pick any random, cheap barbell.

In fact, you should put at least as much thought into which barbell you buy as which power rack you buy. That doesn’t necessarily mean your bar should cost more than your power rack.

But the minimum price range for a quality barbell that you won’t “outgrow” after two or three years of good strength progress is $200-$350 retail. You can get another boost in quality and performance when you get into the $350-$500 range; the best value bars are in this range, in my opinion. And if you want the best of the best, you can expect to pay $500+.

The increase in quality and performance of $500+ bars vs $300-$500 bars is much less dramatic than the increase you get with $300-$500 bars vs bars under $300.

So if you get a bar in the highest price range, you should have a specific, practical reason why. Otherwise, you may be paying for features that won’t make a difference for your training style and/or experience level.

Power Bars vs Olympic Weightlifting Bars vs Multipurpose Bars

Powerlifting Barbells (i.e. Power Bars)

Powerlifting bars, also called power bars, are made for anyone who does powerlifting style training. This includes competitive and recreational lifters alike. In other words, if your training is centered around the Big 3 lifts (squat, bench, deadlift), a power bar is the only barbell you need.

Power bars have the following features and specifications:

- 29mm shaft diameter

- 20kg weight; sometimes 45lbs

- Stiff; No whip:

- IPF markings

- Center knurling

- Aggressive knurling

- Lack of fast spinning sleeves

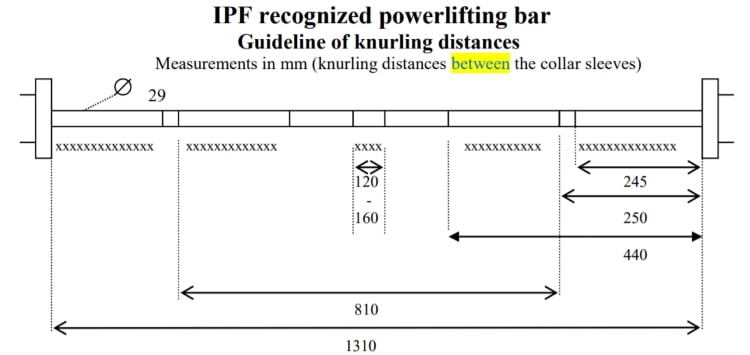

Below is a diagram showing the official International Powerlifting Federation (IPF) barbell specs for measurements between the collars. All IPF-certified power bars must adhere to these specs. And while most power bars aren’t IPF-certified, they still adhere to IPF specs for the most part:

To summarize the diagram above and add a couple additional items, the key IPF bar specs include:

- 20kg (44lb) barbell weight

- Shaft diameter must be between 28-29mm; in practice, it’s 29mm

- Distance between the knurl marks is 81cm (~31.9 in)

- Distance between the sleeve collars is at least 1.31m (~51.6 in), and no more than 1.32mm (~52 in); in practice, it’s 1.31m

- Total bar length can be no greater than 2.2m (86.6 in)

Some non-IPF-certified power bars may have one or two specs that fall outside of the official IPF rules. However, any good power bar will be very close, if not the same.

Some deviation from the official IPF specs is common and totally fine, as long as it’s on less important things like:

- Center knurling length: For example, the Vulcan Absolute Power Bar has 4″ center knurling, which is about 3/4″ less than the minimum length according to IPF spec (120-160mm). This makes hardly any practical difference even if you’re training for an IPF competition.

- Bar weight: Some US power bars are 45 lbs instead of 20kg (44 lbs). This might be important for experienced competitive powerlifters. But for most people, the one pound difference won’t matter in a practical sense.

However, you’d want to make sure the more important specs of a bar line up with the IPF spec rules, such as:

- Shaft diameter (29mm)

- Ring markings (81cm apart)

- Distance between the collars (1.31m apart)

These types of specs can influence technique and performance significantly.

Olympic Weightlifting Barbells (i.e. Oly Bars)

First off, it’s important to note that people often use the term “Olympic barbell” to refer to any bar that’s about 7 ft long with ~2” diameter sleeves.

However, an Olympic barbell is technically a bar made for the sport of Olympic weightlifting. The official Olympic lifts used in competition are the snatch and the clean and jerk. There are many other Olympic style lifts and variations used in Olympic style training.

The key features and specs of Olympic weightlifting barbells (i.e. Oly bars) are as follows:

- 28mm shaft diameter for men’s bars; 25mm for women’s

- High whip

- IWF ring marks

- Moderate knurling to aggressive knurling

- Competition Oly bars generally have more aggressive knurling while training Oly bars tend to be more moderate

- Center knurling

- All men’s competition Oly bars have center knurling.

- Some men’s training Oly bars have center knurling, though many don’t because it can cause discomfort when doing lots of training volume, especially high rep sets. There is NO center knurling on women’s Oly competition or training bars.

- Smooth and fast sleeve spin

- Usually the best Oly bars use high quality needle bearings as the rotation system. A notable exception to this is Uesaka’s barbells, which use a “dry metal” rotation system.

- There are still plenty of excellent training Oly bars that use a bushing rotation system. These will usually be cast bronze bushings (not self-lubricating), sintered bronze bushings (self-lubricating) or composite bushings (self-lubricating). If a bar has brass or steel bushing, then you’re looking at a lower quality bar.

- NOTE: Just because a bar uses needle bearings, doesn’t automatically mean it has better spin than a bushing bar. There’s some less-than-stellar needle bearing bars out there and plenty of great bushing bars. That said, the best of the best, and certainly all IWF competition-certified bars, will have bearings (again, with Uesaka bars being the exception that use neither bearings nor bushings).

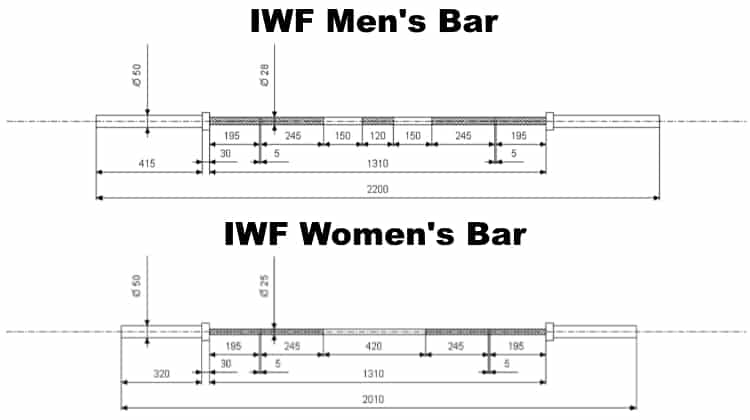

The diagram below shows the official International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) barbell dimensions for men’s and women’s Olympic weightlifting bars. All IWF-certified Olympic barbells must adhere to these specs. Although most Oly bars on the market aren’t IWF-certified, they generally still adhere to IWF specs:

See below for a summary of the key IWF competition bar specs shown in the diagram, as well as a couple other specs not shown:

- Weight of a men’s bar is 20kg (44lbs); weight of a women’s bar is 15kg (33lbs)

- Shaft diameter is 28mm on a men’s bar; it’s 25mm on a women’s bar

- Men’s bars have a center knurling section; women’s bars do not

- Distance between the knurl marks is 91cm (~35.8 in)

- Distance between the sleeve collars is 131cm (~51.6 in)

- Total bar length is 2200mm (86.6 in)

Some non-IWF-certified Olympic weightlifting bars on the market may have one or two specs that fall outside of the official IWF rules. However, any good Olympic weightlifting bar will be very close, if not identical to an IWF-spec’d bar.

Some deviation from the official IWF specs is common and okay as long as it’s on less important things like the center knurling length or the existence/non-existence of center knurling.

For example, IWF men’s bars are supposed to have center knurling. However, it’s not necessary for the Olympic lifts. Plus the rubbing/scraping against the body can actually be a hindrance during training, especially when you’re doing multi-rep sets. Recently, some manufacturers have made Olympic WL specific-bars without any center knurling.

However, you’d want to make sure the more important specs of a bar are in line with the IWF specs, such as the shaft diameter (28mm for men; 25mm for women) and ring markings (910mm apart for both men’s and women’s bars), as those will make a difference in performance.

Multipurpose Barbells (i.e. CrossFit Bars, Hybrid Bars)

Multipurpose or CrossFit barbells are a mix between powerlifting and weightlifting bars. They serve the market of lifters who want one bar that can be used for powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting movements. Often times, this means CrossFitters. However, it’s appropriate for any lifter who wants a general purpose barbell.

The key features and specs of multipurpose barbells include the following:

- 28.5mm shaft diameter, sometimes 28mm for men’s multipurpose bars; always 25mm for women’s multipurpose bars

- Dual knurl markings (IPF/powerlifting markings AND IWF/weightlifting marking)

- Moderate whip

- Mild to moderate knurl

- No center knurl; or sometimes a passive center knurl (the vast majority have no center knurl at all)

- Smooth sleeve spin; quick rotation, but not necessarily super fast or long-lasting

- Multipurpose bars almost always use bushings; the better multipurpose bars will use cast bronze bushings (not self-lubricating), sintered bronze bushings (self-lubricating) or composite bushings (self-lubricating); cheap, low quality bars will use brass bushings

Key Barbell Specification Categories

In this section I’ll define and discuss each specification category. I’ll tell you which specs to look for in the different barbell categories.

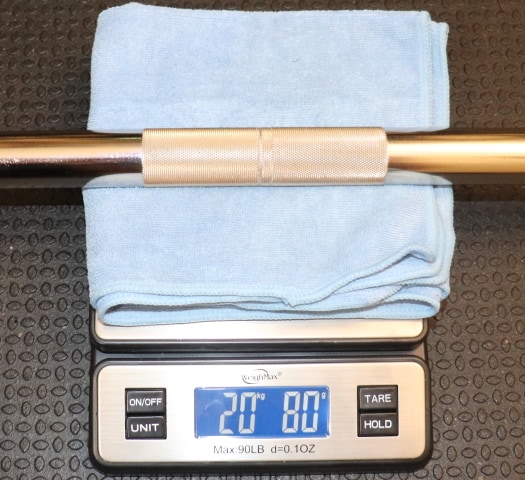

Weight

20 kg, or sometimes 45 lbs, is the weight for:

- Men’s Olympic weightlifting bars (always 20kg)

- Men’s multipurpose bars

- All power bars (there aren’t different power bars for men and women)

15 kg, or sometimes 35 lbs, is the weight for:

- Women’s Olympic weightlifting bars (always 15kg)

- Women’s multipurpose bars

Shaft Diameter

28mm – Men’s Olympic Weightlifting Barbells (and Sometimes Men’s Multipurpose/CrossFit Barbells)

All men’s Olympic weightlifting bars have a 28mm diameter. That’s the IWF standard. This is the thinnest men’s barbell shaft size out of all the different types of barbells (not counting 27 mm deadlift bars, which I won’t discuss since they’re specialty bars).

There main reason for the relatively thin shaft is that it allows for the optimal amount of whip. You want a good amount of whip in the bar for performing the Olympic lifts. The whip does a couple of things in the Olympic lifts:

- It allows the bar to flex when you catch it in the clean position on your collar bone. This means it hurts less because the bar bends, which reduces the impact compared to if the bar were stiff.

- You can transfer the momentum from the bar into your lift by taking advantage of when the bar is whipping upwards.

Shaft diameter isn’t the only thing that determines the amount of whip a bar has. The steel and the metallurgy process used during manufacturing also plays an important role.

Another reason for the relatively thin shaft is that it allows most men do get a solid grip on the bar, even if they have smaller than average hands.

28.5mm – Men’s Multipurpose/CrossFit bars

Although there’s plenty of men’s multipurpose bars that are 28mm, many if not most are 28.5mm. This makes them half a millimeter thicker than men’s Olympic weightlifting bars and half a millimeter thinner than powerlifting bars. This does a few things:

- It allows the bar to have higher tensile strength than a comparably spec’d 28mm bar.

- It also allows the bar to have the right amount of whip. That is, less whip than a 28mm bar, but more whip than a stiff 29mm power bar. Bar diameter isn’t the only factor contributing to whip/stiffness, but it’s a big one. With a multipurpose bar, you’ll probably be doing the Big 3 lifts and some Olympic style lifts. You don’t want too much whip in the bar on squats and bench in particular, but you do want enough whip where it’s essential: on Olympic lifts like the snatch and the clean and jerk, and their many variations.

- It lets you get a better grip than if it were 29mm diameter like a powerlifting bar. A half-millimeter difference is small, but it makes a noticeable difference in grip, especially if you don’t have large hands. Having proper grip is particularly important on Olympic-style lifts that involve shifting your grip around the bar during the movement.

25mm – Women’s Olympic Weightlifting Barbells & Women’s Multipurpose/CrossFit Barbells

Women on average have significantly smaller hands than men. As such, their Olympic and CrossFit bars are 3mm smaller in diameter. That’s a major difference in terms of how thick a bar feels in you hand. The skinnier shaft makes it much easier for women to use, particularly on Olympic-style training that involves shifting your grip around the bar at different points in the lifts.

29mm – Powerlifting Barbell

With a 29mm thick shaft, power bars are 1 mm thicker than men’s Olympic bars and 0.5 mm thicker than most men’s multipurpose/CrossFit bars. All else being equal, the extra thickness makes a bar stronger and more rigid, which is important when doing powerlifting movements.

NOTE: There is one notable power bar that is thinner than 29mm. It is the Buddy Capps Texas Power Bar, which uses a 28.5mm shaft.

>29mm – Other

Barbells that are thicker than 29mm are almost always super low quality and should be avoided at all costs. NOTE: This does not apply to specialty bars like squat bars and axle bars, which are thicker by design.

Tensile Strength (PSI)

Tensile strength is the amount of stress a barbell can take before it fractures. It’s measured in pounds per square inch (PSI). This is the standard spec that manufacturers use to advertise the strength of their barbells.

The video below shows how Vulcan Strength uses a hydraulic press to measures tensile strength:

Technically, yield strength would be a better metric to quantify barbell strength in a more practical way. That is because yield strength is the amount of stress a barbell can take before it bends permanently. A bar is way more likely to bend permanently than it is to actually fracture. Unfortunately, it’s rare for manufacturers to test for and list yield strength.

But the good news is that tensile strength and yield strength usually correlate well. At least this is the case for bars that are well made. It is possible to have a high tensile strength bar with disproportionately low yield strength. However, those are likely to be cheap bars from unreliable or no-name brands.

Higher tensile strength bars tend to experience less oscillation. Or at least there is a correlation. To be clear, tensile strength doesn’t affect how much a bar will bend (statically) when weight is loaded on. Two bars with vastly different tensile strengths that are otherwise identical will bend the same amount when loaded with the same amount of weight.

Rather, the tensile strength seems to affect how much up or down movement (i.e. oscillation or whip) the bar will experience during acceleration or deceleration…

…That said, you can still have very whippy bars with high tensile strength (e.g. the Vulcan Men’s Absolute Stainless Steel Olympic Barbell has a lot of whip at 240k PSI). This is because tensile strength isn’t the main factor in whippiness. Bar diameter is a much bigger factor.

The majority of decent barbells, regardless of the type of barbell, tend to range between 190k – 205k PSI tensile strength. However, there are many that fall above and below this range. Here’s a general breakdown of the tensile strengths for the different types of bars:

- The highest PSI bars on the market are power bars, with the Kabuki Strength New Generation Power Bar taking the top spot at an impressive 258k PSI tensile strength.

- While Olympic weightlifting bars don’t have the highest PSI’s on the market, there are a lot of Oly bars that are significantly above the average range (e.g. several models from Rogue, Eleiko and Werksan that are all 215k PSI).

- Multipurpose bars tend to cluster around 190k PSI.

Finish

There are many types of barbell finishes available. I’ll discuss some of the most common ones in the sections below.

Black oxide

Black oxide is only mildly resistant to oxidation. It is only a step up from bare steel in this regard, so frequent maintenance is required to prevent rusting.

A major positive of this finish is that it’s excellent for preserving the natural grippiness of the knurling compared to other types of finishes. It’s close to a bare steel or stainless steel bar in this respect. I believe this is due in part to the texture of the black oxide, which has a dry, almost tacky feel to it. Another factor is that it’s a super thin finish (technically zero depth since it’s a conversion coating), so it doesn’t fill in the knurling and make it feel duller.

Black oxide holds chalk better than most finishes, which is great if/when you need to use chalk. Though, many times chalk won’t even be needed thanks to the natural grippy feel of the finish, particularly if the bar also has sufficiently aggressive knurling.

Black oxide is one of the lower-cost options among the various finishes.

When you do use chalk on a black oxide bar, just remember to not let it build up for too long before cleaning it out. As mentioned earlier, regular maintenance is required for this finish. Since chalk buildup will accelerate oxidation, you’ll need to clean the bar even more frequently if you regularly use chalk.

Over the long term, black oxide will fade noticeably where you hold onto the bar — even with proper maintenance.

Overall, black oxide is a great finish to have if you’re willing to do maintenance, but should be avoided if you’re in a high humidity gym, and especially if you’re in a coastal environment.

Bright zinc

Bright zinc is highly resistant to oxidation in most conditions. Any oxidation that occurs will have to go through all of the zinc plating before the underlying steel is affected.

This finish can do well even in moderately humid areas. But if it’s highly humid, then oxidation will occur. If you’re not working out in a highly humid environment, then only cerakote and stainless steel is more resistant to oxidation. However, if you are training in a highly humid area, then hard chrome is more resistant, followed by cerakote and stainless steel as the most resistant.

The main drawback of bright zinc is that it feels less natural than black oxide bars. This is because a zinc plating is thicker than a black oxide and thus will fill in the knurling and make it feel less aggressive. That said, the bright zinc coating is not as thick as, say, hardened chrome. So, it’s possible to get a good a bright zinc bar that’s sufficiently grippy if the manufacturer uses the right knurling pattern.

Bright zinc costs more than black oxide, but it’s still an economical choice.

You can expect the the zinc to tarnish over time, but the underlying steel will remain protected for a long time assuming you take proper care of it. It doesn’t require as frequent maintenance as black oxide, but maintenance should still be done regularly.

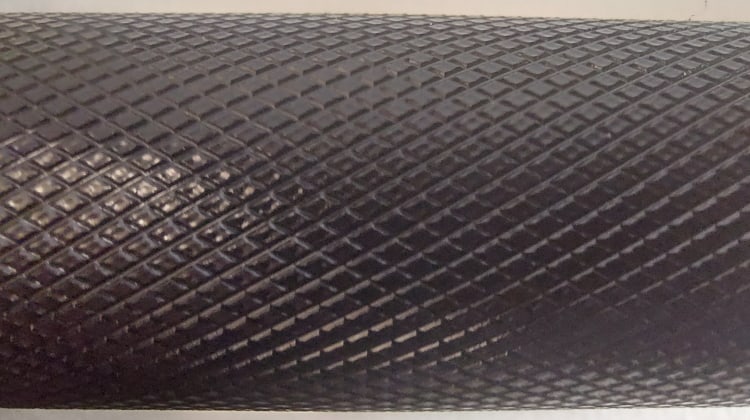

Black zinc

The black zinc finish is created by first plating the bar with bright zinc. A black chromate conversion coating is then applied on top. While the black chromate technically does provide some extra oxidation resistance, it’s really quite minimal in practice. The main reason for the black chromate is the color.

So, black zinc and bright zinc are virtually the same when it comes to oxidation resistance: they’re both excellent in all but highly humid conditions.

However, black zinc falls short compared to bright zinc in a couple key ways. First, the feel of a black zinc bar is less natural and grippy than a bright zinc bar. I believe this is mostly because the black chromate conversion coating is slicker than plain bright zinc.

The thin black chromate coating is directly related to black zinc bars being notorious for fading relatively quickly and eventually developing an odd greenish tint.

The only reason to go with black zinc over bright zinc is to get the black color instead of silver. Just know that this color is only guaranteed initially and there’s a decent chance its color will get a bit greener over time.

All that said, black zinc isn’t the end of the world. If the bar has most of the other features you want, it can work. But if you have other options, you can do better. If you get a black zinc bar, you should maintain it at least as much as a bright zinc bar, if not more often, to try to preserve the top black layer for longer.

Hard Chrome

Hard chrome comes as either polished chrome or satin chrome. There’s no functional difference.

Polished chrome is simply a shiny silver since the non-knurled parts of the shaft are polished after applying the chrome. Whereas, the satin chrome is not polished, so it’s more of a matte silver.

Hard chrome is a robust finish. It is highly resistant to oxidation. In fact, while zinc may be on par if not slightly more oxidation resistant in low to moderately humid conditions, hard chrome outperforms zinc in highly humid environments.

Additionally, hard chrome tends to last longer on the bar than zinc, which is prone to wear and fading. Whereas, hard chrome is highly resistant to scratching, chipping and fading.

One very cool thing about hard chrome is that it can actually increase the tensile strength of the bar. Generally, this bolstering of tensile strength will be more pronounced on higher quality, more expensive chrome bars. This is because the finishing process during manufacturing can influence the quality of the chrome plating.

Hard chrome has a pretty natural grip feeling compared to bright or black zinc. However, you’ll find that a chrome bar with milder knurling may have less grip than you’d expect. This is because hard chrome is a thick finish that will fill in the gaps around the knurling, making it smoother than if a thinner finish were used. So in most cases, you’d want a chrome bar with knurling that’s relatively deeper to compensate for thick coating.

Overall, hard chrome is a top tier finish for most applications and environments. You’ll pay for it accordingly, as it’s a jump up in price from zinc and black oxide.

NOTE: There’s also decorative chrome. This is different than hard chrome. While it can look similar, it’s less robust in terms of its resistance to oxidation and abrasions. Of course, it’s also cheaper. Some manufacturers will falsely call decorative chrome hard chrome, so be aware of that possibility. If the price seems too good, chances are it’s decorative chrome.

Cerakote

Cerakote is a polymer-ceramic composite coating that can be applied in any color under the sun.

Cerakote has seen widespread adoption as a barbell finish in just the last few years. A big reason for the popularity of cerakote bars is the aesthetics of having bright colors, patterns and even graphics on the bars.

The other major reason for the adoption of cerakote is its properties as they relate to oxidation resistance, abrasion resistance, natural tack/grip and overall bar shaft strength/durability. Cerakote is comparable to hard chrome in many of these categories; sometimes performing better than chrome and sometimes performing slightly worse.

For example, both cerakote and hard chrome have a natural feel, but cerakote is notably grippier. Both cerakote and hard chrome are chip/scratch resistant, but I’ve seen more reports of chips and scratches on cerakote than I have for hard chrome. Both cerakote and hard chrome are corrosion resistant, but cerakote can easily handle highly humid areas that chrome would suffer in.

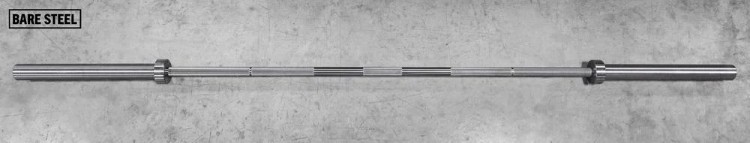

Bare Steel (Carbon Steel)

Bare steel, also known as raw steel, is actually not a type of finish. Bare steel bars are unfinished bar. The shaft itself is made of carbon steel.

The knurling has a more natural and grippy feel than finished bars — since there’s nothing between the steel and your hand. Another benefit is that it’s cheaper than other finishes, all else being equal.

The downside is that this type of bar requires a lot of maintenance to minimize rust. This is especially the case if you workout in a moist area, and even moreso if you’re near the coast, since the salt in the area can accelerate corrosion. Even with frequent maintenance, a bare steel bar will inevitably develop a patina, though this can give it a unique look.

Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is another type of bare steel. That is, the shaft is made from stainless steel instead of carbon steel; with no finish on top of it. So, it feels just as natural and grippy as a regular bare steel (carbon steel) bar.

Also, these bars are stainless. They’re rust resistant, so minimal maintenance is required, even compared to finished barbells. However, the steel used for the bar shaft is significantly more expensive than the carbon steel used in most barbells. Accordingly, you can expect to pay a premium for a stainless steel bar.

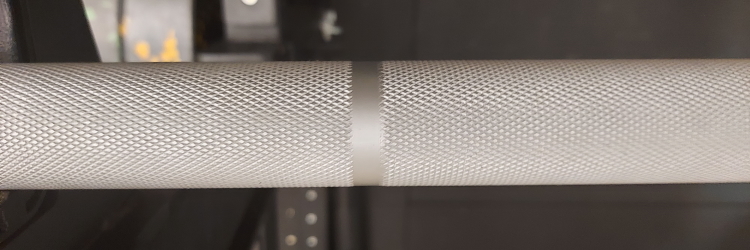

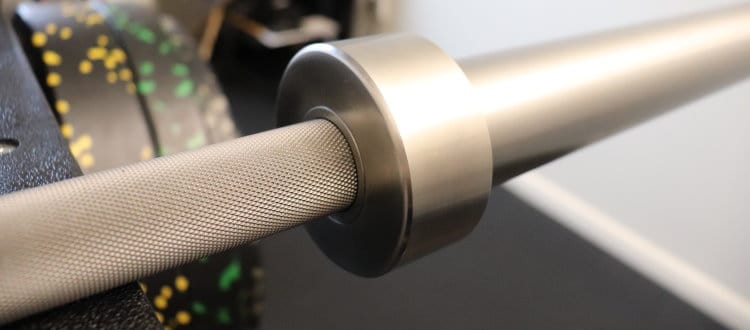

Knurling

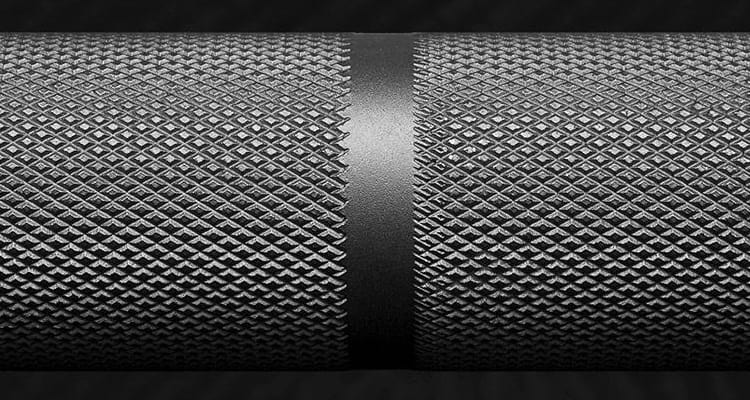

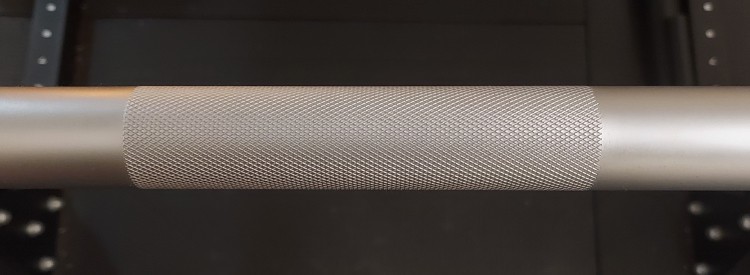

Comparing Knurling

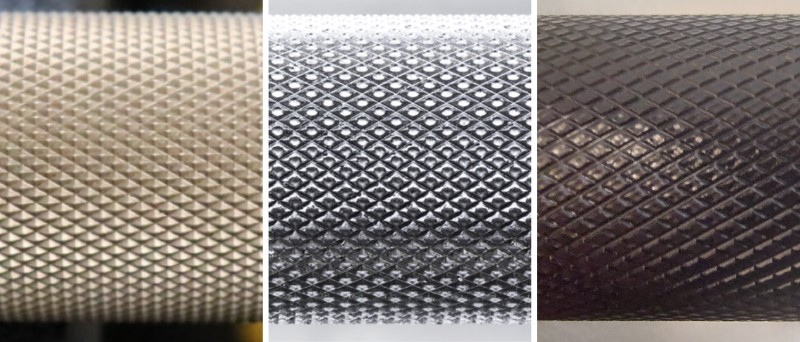

There is no standardized knurling rating system for barbells. The main factors that would go into classifying such a classification system for knurling would be:

- Depth: How deep the knurl is cut into the bar.

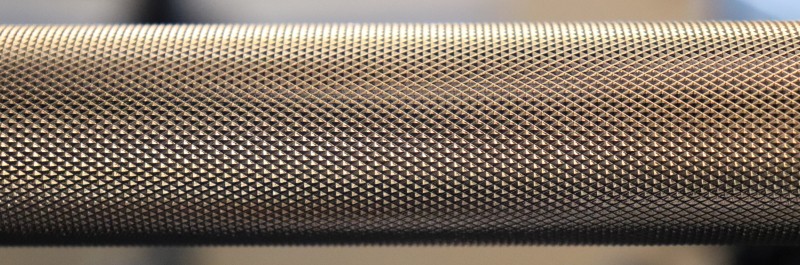

- Style: The style of 3D shape of the knurl point. There are 3 basic styles:

- Mountain-style knurl points, which come to a point at the top (like a mountain peak).

- Volcano-style knurl points, which are pitted or scooped out at the top (like a volcano).

- Flat knurl points, which are plateaued.

- Density: The number of knurl points per square inch.

The number of combinations you’d get with the above characteristics would be extremely high. And it would be very hard to analyze then categorize them in a meaningful way with regard to the strength of the knurling. And that’s before you also consider the much less quantifiable factor of:

- Bar finish: The finish used on the bar — or lack of one for bare steel bars — will greatly influence the “feel” of the bar, which is directly related to the perceived knurl strength. The finish’s texture is tackier/grippier (e.g. black oxide, cerakote) or smoother (e.g. black zinc, bright zinc). The thickness of the finish when applied to the bar can also change the feel of the knurling by effectively making it shallower than it actually is (e.g. hard chrome is a thick finish, so it will fill in the gaps between the knurl tips more than a very thin finish like black oxide).

The complexity of all the above factors makes an objective standardized knurl rating system impossible. This is largely why knurling the most difficult specification to judge when you’re shopping for a barbell online.

You have to rely on either:

- What the manufacture says. This isn’t always helpful. First off, different manufacturers use different terms to describe the knurling. Second, their description of the knurling may be relative to their other bars as opposed to other bars on the market.

- What other owners of the bar have to say about it. This is better to go by than the manufacturer, particularly if you can find multiple people saying the same thing. Still, it’s subjective. What may be aggressive knurling to one person may be moderate to someone else.

- If you can find clear photos of the knurling, that also helps — whether from the manufacturer or other owners.

Now that I’ve told you it’s next to impossible to truly judge or classify the feel or strength of a bar’s knurling without using it yourself — I’ll do my best to give you some rough guidelines on the different types of knurling:

- First, I’ll break it down into three categories by the strength, or aggressiveness, of the knurling, and do my best to describe each.

- Then I’ll tell you the applications for each type of knurling and who it’s best for.

- Lastly, I’ll give you examples of bars in each knurling category.

Mild Knurling

Mild knurling is very soft and shallow cut. Some may call it passive. On the lowest end of the “mild spectrum,” you could even call it dull.

Some of the cheaper no-name multipurpose bars on the market may be classed as mild. These can be okay for high-rep sets, but even they leave something to be desired. Heavier work on such bars almost requires a boatload of chalk, or straps. Most barbells that I talk about don’t fall into the mild category, unless they have passive center knurl.

Note that some other people may consider mild knurling to be what I call medium knurling. There’s no objective rating system so it’s all about context and who you’re listening to.

Medium Knurling

Sometimes called standard or moderate knurling, medium knurling is most commonly found on multipurpose, or CrossFit-style barbells. It’s not so sharp that it tears up your hands on the high rep pulling exercises or Olympic lifts that are commonplace in CrossFit. But it is strong enough for most people to get a decent grip even on relatively heavy deadlifts or Oly lifts.

However, it’s not ideal for max or near-max deadlifts, but you can get away with it, especially if you chalk up. If you’re not into powerlifting-style training and you can only get one barbell, then I’d recommend seeking one out with medium knurl pattern.

Medium knurling is also sometimes found on Olympic weightlifting barbells. Specifically, it’s common on the “training” Oly bars. This less intense knurling is preferred by many Olympic weightlifters, who commonly do multiple 1-2+ hour sessions of mostly pull-based lifts throughout the week. These lifts also usually involve the hook grip. As you could imagine, knurling that’s not aggressive but also not too mild will allow these lifters to train effectively without tearing up their hands and thumbs.

The “competition” Olympic lifting bars tend to have more aggressive knurling. Of course, these bars are mostly meant for use in competition (or training in competition-like conditions). There are also some aggressive “training” bars out there, such as those from Eleiko.

Here are some of the best barbells on the market with medium knurling:

- American Barbell California Bar (on the lighter end of the medium spectrum, but still very grippy)

- Vulcan One Basic Barbell

- Vulcan Elite V4.0 Bushing Barbell

- Fringe Sport Wonder Bar

- Rogue Ohio Bar

- Rogue Euro WL Bar

Moderately Agressive Knurling

Moderately aggressive knurling is knurling that has some bite to it without being decisively deep or sharp. It’s that sweet spot between medium knurl and fully aggressive knurl.

This type of knurling is found more commonly on power bars and Oly bars. It’s less common on multipurpose bars, which are overwhelmingly in the medium knurl category.

Here’s some of the best barbells on the market with moderately aggressive knurling:

- Fringe Sport Power Bar

- Uesaka Bars

- Fringe Sport Hybrid Bar (some people may consider this more on within the “medium” knurl spectrum, but it’s at least close to being moderately aggressive)

- Matt Chan Bar

Aggressive Knurling

Sometimes called sharp or deep knurling, aggressive knurling is a typical characteristic of powerlifting bars. The idea is that you want the strongest grip when using the heaviest weights. Having aggressive knurling is most important for deadlifts, particularly when doing max or near-max weight.

An aggressive knurl may feel sharp in your hands during heavy deadlifts, but it keeps the bar from slipping. It’s also beneficial on other heavy accessory pulling movements that powerlifters often do, such as RDLs, barbell rows, block pulls and more.

People with smaller hands will benefit from a sharper knurl, since smaller hands generally means a weaker grip (all else being equal).

There are some aggressive bars that are deep, but have a bit less sharpness. These are the bars that utilize the volcano-style knurl (the knurl points are pitted at the top), which I showed in the “Comparing Knurling” section earlier.

Here are some of the best barbells on the market with aggressive knurling:

- Vulcan Black Oxide Absolute Powerlifting Barbell

- Rep Fitness Stainless Steel Deep Knurl Power Bar EX

- Kabuki Strength New Generation Power Bar

- Vulcan Stainless Steel Absolute Power Bar

- Buddy Capps Texas Power Bar

- Rogue Ohio Power Bar

Center Knurling

No Center Knurling

Some bars have no center knurling at all. These are usually multipurpose barbells or women’s Olympic barbells. Some men’s Olympic training bars also lack a center knurling.

The benefit of no center knurling is that your torso and chest don’t get scraped on Olympic lifts. The disadvantage is that you don’t have any grip to help keep the bar on your traps during squats, lunges or any behind the neck exercises.

Passive Center Knurling

Passive center knurl, sometimes called recessed center knurling, is less common than aggressive center knurling and no center knurling. However, it can be quite a nice feature if you’re seeking a more versatile bar that will let you squat (but won’t tear up your traps) and will also let you do some Olympic movements without ripping up your torso.

Passive center knurl is usually found on men’s Olympic barbells and some multipurpose bars. More rarely, you’ll find it on some power bars.

Some popular bars with passive center knurling include:

- Fringe Sport Hybrid Barbell

- Rogue Matt Chan Bar

- Vulcan Black Oxide Absolute Power Bar — The center knurl here on this bar is still be considered somewhat aggressive, but it is much less aggressive than its outer knurling. So, doing power cleans would still be uncomfortable. However, it makes back squatting much more comfortable on the traps while still giving enough grip. See my full review.

Aggressive Center Knurling

Aggressive center knurling is common on powerlifting barbells. Its purpose is to keep very heavy loads secure on your back for squats.

Pro tip: Don’t squat shirtless if you get a power bar with aggressive center knurling.

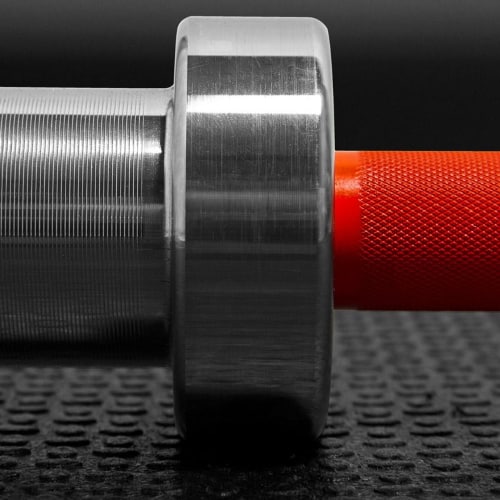

Rotation System

The two rotation systems you’ll find in 99% of barbells on the market are bushings and bearings. These two components serve the same basic function. They reduce friction between the bar shaft and the sleeve to produce rotation.

The mechanisms of bushing and bearing systems are different. They differ greatly in the amount of spin they provide.

There are multiple types of bushings and bearings. Each type has different characteristics that make them better or worse depending on the training application.

I’ll go into detail about bushings and bearings below:

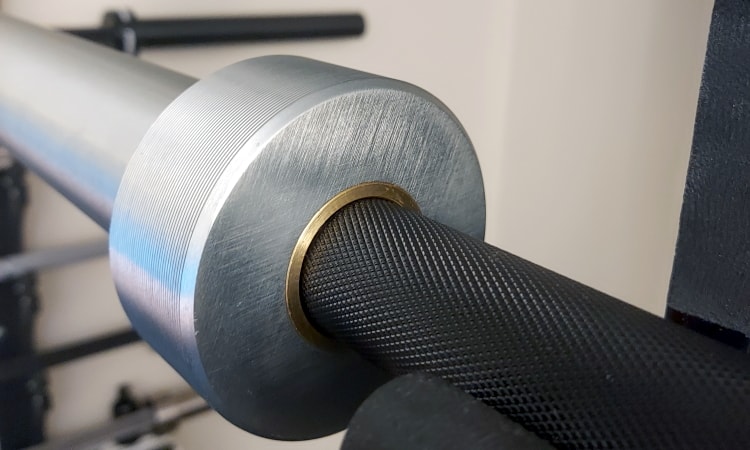

Bushings

A bushing is a smooth and solid cylindrical ring. It fits over the bar shaft. The sleeve fits over the bushing.

There are many different types of bushings, most commonly including:

Cast Bronze Bushings

These are made of non-porous bronze, so they’re not self-lubricating. They’re strong and durable.

They can spin very smoothly, performing best under light to moderately heavy loads. They can do well under heavy loads, but sometimes lose some smoothness compared to other options.

You’ll have to manually lubricate them more frequently to maintain the amount of spin they have as when the bar is new.

This type of bushing is excellent for powerlifting bars. It won’t spin excessively under heavier loads on the power lifts, where minimal spin is most important. You don’t need to lubricate these bushings frequently in the powerlifting context. The loss of oil over time in cast bronze bushings means less spin. This is totally fine if not beneficial for heavy powerlifting movements.

Cast bronze bushings also work well for multipurpose/CrossFit bars. The only only caveat is that you have to maintain them more frequently. It’s not that hard to do. It just takes a couple drops of oil on each side every couple of months depending on how regularly you use it.

Sintered (i.e. self lubricating) bronze bushings

Sintered bronze bushings are manufactured by heating powdered bronze to fuse the particles together. The finished result is a bushing with tiny holes throughout it that impregnate the bushing with oil. The oil is stored inside and can pass through either side. This maintains a consistently low-friction surface.

The spin is more consistent over time because the bushing will always have enough lubrication. Whereas, you’ll notice the rotation slowly deteriorate over time with cast bronze bushings until you manually oil it.

You’ll rarely if ever need to manually oil the sleeves on a sintered bronze bushing bar. Sintered bronze bushings are overall the best bushing in terms of spin performance (i.e amount of spin, responsiveness and consistency of spin).

Composite bushings have a slight performance advantage under very high loads. Sintered bronze wins everywhere else. Does that means they’re the best bushing for every bushing bar? Not necessarily.

Cast bronze may have a slight advantage on power bars. This is because they’ll lose spin over time, which is good for slow and heavy powerlifitng movements.

Additionally, composite bushings may be better for multipurpose barbells if noise reduction is a priority for you. They’re also good if you want the most durable/impact-resistant bushings as possible.

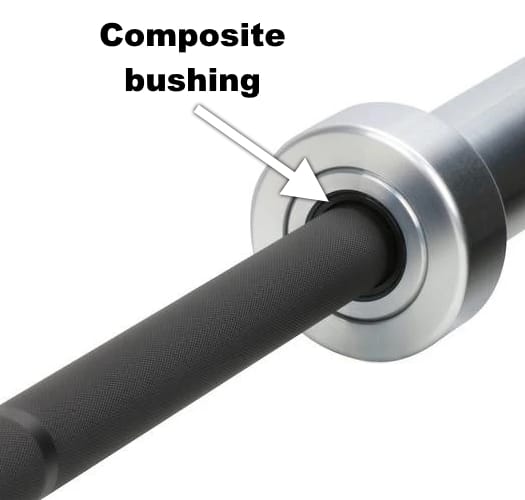

Composite bushings

Composite bushings are made of a plastic composite material. These are self-lubricating like the sintered bronze bushings. This means they require little to no maintenance in terms of oiling.

Composite bushings have some unique advantages over bronze bushings:

- They’re significantly quieter when you drop the bar. This is because you have a plastic buffer between the shaft and sleeve instead of a metal buffer. This is a big plus if minimizing noise is important for your home gym (sleeping baby, neighbors, etc.).

- They’re more impact-resistant. You likely won’t run into a scenario where the extra protection from impact will make a difference compared to a good bronze bushing. Still, it’s better to be too robust than not robust enough.

- It provides a more consistent and smoother rotation than both sintered and cast bronze bushings under super heavy loads. This is because it’s made from a harder and stronger composite material that won’t slow down or spin inconsistently even at extreme weights. The softer bronze material that will experience this at high enough weights. The bronze bushings aren’t unusable at these weights. It’s just that the spin isn’t ideal. Of course, you should probably get a needle bearing bar if you’re using super heavy weights on the Oly lifts.

So are composite bushings better all around? Actually, no.

They are very good overall. However, sintered bushings beat them out in one place: the amount and quality of spin in low to moderately heavy range. This is the range where most people will be doing most of their lifts.

You may only notice the difference in rotation between these two types of bushing bars if you’re experienced with the Olympic lifts. The difference is subtle, but it’s there.

Brass bushings

Generally, you should avoid these. They’re softer than bronze and are thus more likely to deform. They will spin less reliably under load.

The only brass bearing bar I’d recommend is the Texas Power Bar. It’s a time-tested powerlifting bar. It can get away with the brass bushing, since it’s a power bar, where spin is less important. Plus it has other solid features that make it an overall reliable bar.

If you see brass bushings on an Olympic bar or a multipurpose bar, think twice before buying. I know of one decent multipurpose bar with brass bushings. It’s the Bells of Steel Utility Bar. But it’s billed as a budget bar so the brass bushings are forgivable for the price. Go for it if you’re on a tight budget.

Bearings

A bearing consists of a ring with rolling pieces inside (e.g. needles or balls). These pieces enable rotation between two mechanical components.

The bearing slides over the barbell shaft. The barbell sleeve sits atop the bearing. The bearing separates the bar sleeve and bar shaft. The rolling pieces allow the sleeve to spin smoothly around the shaft.

The rolling pieces in the bearing can either be needles or balls. However, ball bearings in barbells are rare. If you see a bar with ball bearings, that bar is cheap and low quality.

Needle bearings are the standard. They can handle more radial load. They are much more resistant to radial impact than ball bearings. They are simply more durable and better overall for use in a barbell. When I refer to bearings going forward, you can assume I’m referring to needle bearings.

Generally, bearing bar sleeves spin faster and more smoothly than bushing bar sleeves. This is why nearly all competition Olympic weightlifting bars use needle bearings for their rotation systems (exception: Uesaka’s dry metal system). Similarly, many training Olympic weightlifting bars use bearings.

Having quality rotation is essential in the sport of Olympic weightlifting. Bearings are the best tool for achieving that.

One downside of bearing bars is their cost. All else being equal, they’re more expensive than bushing bars.

They also require more frequent maintenance than self-lubricating bushing bars. But that’s not a huge deal. It’s just a matter of remembering to occasionally add oil once in a while.

If you plan on doing some Olympic lifting but don’t plan on training like a competitive Olympic lifter, then a good bushing bar is the practical choice.

Bushings or Bearings on Different Types of Bars

Almost all powerlifting bars use bushings. Cast bronze bushings are most common. You want minimal sleeve spin when doing the power lifts. These lifts are typically performed slow and heavy. Too much spin can throw off your technique. Having cast bronze bushings — usually just two per side — gives the bar only as much spin as it needs.

You’ll see multipurpose/CrossFit bars using cast bronze bushings, sintered bronze bushings or composite bushings.

The better multipurpose bars tend to have sintered bronze or composite bushings. However, having either of these does not necessarily mean it’s a good bar. Similarly, there are plenty of good quality multipurpose bars with cast bronze bushings. Just know that with a cast bronze bar, you’ll have to remember to oil them periodically to maintain their spin.

Less frequently, you’ll also come across multipurpose bars that use both bushings and bearings, or just bearings. Sometimes, these bars are great (e.g. Eleiko XF Bar). Other times, they’re average or even low quality bars that use cheaper bearings simply to say that it’s a bearing bar.

Olympic weightlifting bars most often have needle bearings. This is particularly the case for Olympic competition bars, which require bearings in nearly all cases.

There are also Olympic training bars. Many of these have needle bearings, too. Yet many others have bushings. Most quality Olympic training bars that use bushings will use sintered bronze bushings (e.g. Vulcan Standard Olympic Training Bar) or composite bushings (e.g. American Barbell Performance Training Bar).

There are some decent lower priced Olympic training bars that use cast bronze bushings like the Rogue 28mm Training Bar. That said, if you’re serious about your Olympic lifts and want a bar that you won’t outgrow in a few years, look for something with a better rotation system.

Composite bushings are very rare among Olympic weightlifting bars. In fact, the only ones I’ve seen are from American Barbell who is known for using composite bushings in all of their bushing bars.

I’d consider an Olympic weightlifting training bar with composite bushings close to par with a sintered bronze bushing bar. It’s arguably better if you want to use it with very heavy weights. It’s definitely the way to go if you want to minimize noise. Of course, it doesn’t beat a comparable needle bearing training bar.

If you’re looking for a good composite bushing Olympic training bar, check out the American Barbell Performance Training Bar.

Knurl Marks

Knurl marks refer to the small gaps in the outer knurling that serve as reference points for grip position.

There are three types of ring mark patterns you’ll find:

- IPF Knurl Marks: These are standard marks for the International Powerlifting Federation, and are thus found on powerlifting bars. The marks are 810mm apart.

- IWF Knurl Marks: These are standard marks for the International Weightlifting Federation, and are thus found on Olympic weightlifting bars. The marks are 910mm apart.

- Dual Knurl Marks: Bars with dual knurl marks have both the IPF and IWF knurl marks. These are seen on multipurpose bars, which are used for both the powerlifts and Olympic lifts.

Barbell Whip

Barbell whip refers to the amount of oscillation a loaded bar experiences when rapidly accelerating or decelerating. Examples include rapidly pulling the bar off the floor on a deadlift or clean, or coming to a stop at the top of an explosive squat.

The amount of whip a bar experiences depends on many factors including:

- Bar shaft diameter: The thinner the shaft, the more whip. Shaft diameter is by far the biggest factor in bar whippiness.

- Tensile strength/Yield strength: Very high PSI bars tend to be more rigid. Bars with lower PSI bars tend to be more whippy.

- NOTE: High and low tensile strength bars have the same amount of static flex, meaning how much a bar bends when loaded but not moving. However, there does appear to be evidence that the amount of PSI affects dynamic flex (i.e. “whip” or oscillation during movement).

- Weight on the bar: The more weight on the bar, the more whip it will have.

- Plate position: If the plates are further out on the sleeves, there will be more whip. For example, if you load on 400 lbs of thick bumper plates, there will be more whip than if you load 400 lbs of thin steel powerlifting plates.

Olympic weightlifting barbells are designed with whip in mind. Barbell whip is essential for the Olympic lifts. You use the momentum of the whip to complete the movements more efficiently and with heavier loads.

Powerlifting barbells are designed to have minimal whip. You want the bar to be stiff when performing the powerlifts with heavy weights. Too much whip can throw off your body position and ruin your lift…

…There is a caveat to this: Deadlifts. Some people prefer deadlifting with whippy bars. This is because you’re able to pull the slack out of the bar and get into a higher position before all of the weight comes off the floor.

If you want a whippy barbell for deadlifting, you may be best off getting a specialty deadlift bar with a 27mm shaft. This would be in addition to your main power bar.

Multipurpose bars have a moderate amount of whip. They’re not so stiff that Olympic lifts are difficult to perform. Yet they’re not so whippy that you can’t do the slow, heavy powerlifts with them. This intermediate amount of whip is achieved mainly through having a 28.5 mm shaft diameter. It is right in between the 28mm Oly bar diameter and the 29mm power bar diameter.

Bar Length

Olympic weightlifting barbells have a strict length measurement because the IWF requires a precise length measurement: 2200 mm for men’s bars and 2010 mm for women’s bars. It’s rare to find Oly bars that don’t match these length measurements.

Powerlifting barbells vary a bit more. This is likely because the IPF doesn’t mandate a precise length measurement. Rather, their guideline is that the length must not be greater than 2200mm. Accordingly, most power bars are 2200 mm long or slightly shorter. Occasionally, you’ll find some that are slightly longer.

There’s no standard length for multipurpose bars. However, most are 2200mm in length, with some being slightly shorter and some slightly longer.

Loadable Sleeve Length

Loadable sleeve length refers to the part of the barbell sleeve that you can actually load weight on. This means the length of the entire sleeve minus the length of the sleeve collar.

The longer the loadable sleeve length, the more weight plates you can fit. Most people won’t be anywhere near strong enough to max out the sleeves with regular cast iron plates. The application where having an extra bit of loadable length is if you use bumper plates since they’re considerably thicker than iron plates.

All Olympic weightlifting bars that conform to IWF standards have a loadable sleeve length of 415mm (~16.33 in) for men’s bars or 320mm (~12.6 in) for women’s bars.

Many powerlifting bars have the same 415 mm (~16.33 in) loadable sleeve length. However, there is more variation with power bars since the IPF doesn’t have a standard length for this dimension. The loadable sleeve length on most power bars falls between 16.25 in to 17 in.

Multipurpose bars are closer to Oly bars in that they tend to stick to the 415 mm (~16.33 in) loadable sleeve length. However, there is a bit of variation. It usually ranges between 16 to 16.5 in.

Most women’s multipurpose bars have a loadable length of around 320 mm (~12.6 in) like women’s Oly bars. Some are longer, but you’re not likely to find one longer than 330 mm (13”).

Regardless of the type of bar, the ones with longer loadable sleeve lengths typically achieve the extra length by having thinner sleeve collars. The only downside of very skinny sleeve collars is that you can sometimes bump the weight plates into the j-hooks racking and unracking the weight if you don’t pay attention.

On a related note, extra skinny sleeve collars have the benefit of making a barbell stiffer. The weight plates are closer to the center of the barbell so there is less flex. This is why you see this feature almost exclusively on power bars, especially competition-style power bars.

Distance Between Sleeves

The vast majority of barbells have a distance of 1310 mm (~51.5 in) between the sleeves. This includes men’s and women’s Oly bars, power bars and multipurpose bars. This is because 1310 mm is the standard shaft length dimension for both the IPF and IWF.

Manufacturer Location

Generally, you’ll get better quality from non-import bars. By non-import, I mean bars that are made in the same country as the company that sells them.

For example, American Barbell is a US company and their bars are made in the US. Likewise, Eleiko is a Swedish company and their bars are made in Sweden. Non-import companies like these generally produce higher quality products because they have more control over the manufacturing process.

On the other hand, imported bars usually come from Taiwan/China. The companies that sell these have less control over the manufacturing process.

There are plenty of excellent imported barbells. And some imported bars are superior to non-imported bars. So, you shouldn’t discount a bar just because it’s an import. Rather, country of manufacture is just one factor to consider.

Many companies don’t sell strictly imported or non-imported bars. It’s common for them to sell imported bars and some bars that are made domestically.

Warranty

The standard these days for most “good” barbells is a lifetime limited warranty. This covers parts and labor. It doesn’t include things like bending the bar shaft from dropping it in your rack.

You need to take into account the company you buy it from when judging their warranty. If they’re unreliable, their lifetime warranty likely is, too.

There are some good barbells with warranties that cover just a few years, but these are usually entry-level bars.

Conclusion & Further Reading

That’s it! You now have all the knowledge you need to intelligently judge the features and specs of any given barbell.

I’ve put together a few guides where I’ve written and compiled short reviews of the best barbells for each of the 3 main types of barbells (power bars, Oly bars, CrossFit bars). Now that you know which type of bar you want, these pages will help you choose the best barbell for your home gym:

Also, be sure to check out my barbell comparison chart to help in comparing specs of some of the best barbells on the market.