The biceps brachii (L. biceps, two-headed [bis, twice ; caput, head] ; G. brachion, arm.), commonly known as the biceps, is the prominent two-headed muscle of the arm.

It acts on the elbow, forearm and shoulder, with it’s main role being a synergist in elbow flexion.

Note: The biceps is most active in elbow flexion when the forearm is supinated, and when the shoulder is neutral or extended. The brachioradialis takes over if the forearm is neutral or pronated (e.g. hammer or reverse curls). The brachialis takes over if the shoulder is flexed (e.g. preacher curl).

Located in the anterior compartment of the arm, the biceps brachii is outermost muscle on the front of the upper arm, lying superficial to the brachialis.

The biceps are arguably the most popular muscle group on the human physique, especially among guys new to lifting. This is not surprising, though, considering the following…

- They’re on front of your body, so you can see them when you look down or stare vainly in the mirror.

- They stand out and add an aesthetic emphasis to the physique, despite being a relatively small muscle.

- When someone asks you to “flex” or “make a muscle,” you’re expected to brandish your biceps.

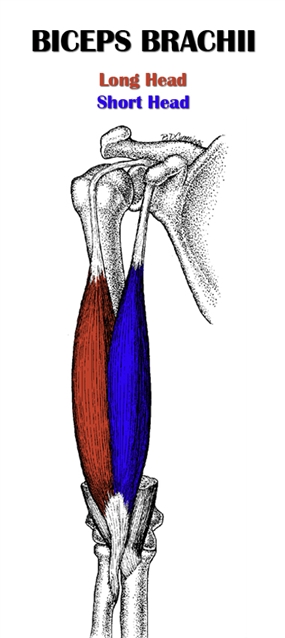

The biceps brachii consists of a short (inner) head and a long (outer) head.

The short head originates from outer tip on the top of the scapula, and the long head from just above the shoulder socket on the scapula.

The parallel-oriented fibers of each head run distally down the humerus and insert on the anterior proximal radius.

Fun Fact: “Biceps” (not “bicep”) is the correct spelling for the singular form of the word. This is because the suffix, -ceps, refers to multiple heads of a single muscle. So, even though it sounds weird, the sentence, “My left biceps is lagging, bro!” is grammatically correct. The same concept applies to any muscle ending with -ceps, like triceps and quadriceps.

Table of Contents

Also Called

- Biceps

- Bis

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Short Head | Long Head |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Tip of the coracoid process of the scapula | Supraglenoid tubercle of scapula |

| Insertion |

|

|

| Action |

|

|

| Nerve Supply | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C6) | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5-C6) |

Exercises

Note: The exercise lists below only contain movements that most directly train the biceps brachii. However, the biceps brachii are also get worked hard, though less directly, during brachialis exercises (e.g. preacher curl, concentration curl), brachioradialis exercises (e.g. hammer curl, reverse curl) and back exercises (e.g. chin up, underhand row).

Barbell Exercises

- Curl

- Seated curl

- Drag curl

Dumbbell Exercises

- Standing curl

- Seated curl

- Incline curl

- Drag curl

Cable Exercises

- Curl

- Supine curl

- Drag curl

Machine Exercises

- Seated curl

- Incline curl

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques

Stretches

- Behind-the-back biceps stretch

- Doorway biceps stretch

- Floor seated biceps stretch

- Wall biceps stretch

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

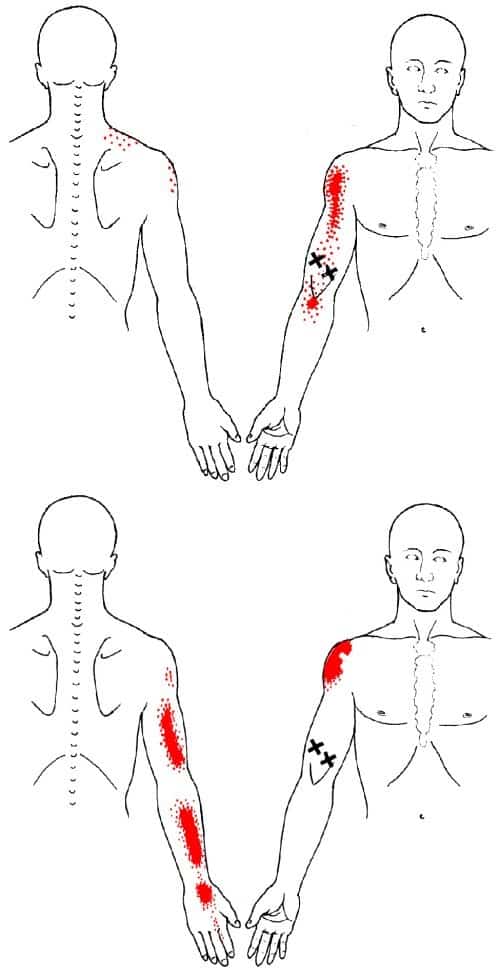

When using these techniques, give special attention to the common trigger points shown in the image below.

Tool

- Foam roller on biceps

- Lacrosse ball

- Sprinter Stick

- Medicine ball

Common Issues

- Overactive/Short Biceps Brachii: The biceps tend to be overactive and short in many people due to spending so much time in elbow flexion (e.g. typing, texting, playing video games). This is further exacerbated by the common practice of excessive biceps training. The overactive/short biceps reciprocally inhibits triceps to an extent, causing it to become somewhat inhibited/lengthened. This imbalance between the biceps and triceps will eventually slow your progress on isolation arm exercises as well as any compound upper body push or pull exercises. Additionally, overactive biceps tend to take over upper body pull movements (e.g. rows, chin ups), resulting in poor form and reduced back muscle activation.

- Biceps Tendinosis: Biceps tendinosis is a non-inflammatory condition characterized by degeneration of the biceps tendon and associated pain. This not to be confused with the tendinitis, or inflammation of the tendon, which is actually much more rare. Biceps tendinosis typically results from overuse of the biceps tendon from repetitive and/or excessively strenuous movements. There are two basic types of biceps tendinosis:

- Distal biceps tendinosis, which affects the biceps tendon that inserts on the forearm. It is caused by repetitive and/or excessively overloading of the tendon during elbow flexion movements.

- Proximal biceps tendinosis, which affects the biceps long head tendon that attaches just above the shoulder socket on the scapula. It is caused by repetitive and/or excessively overloading of the tendon during arm elevation movements. The root cause of biceps tendinosis is typically poor scapular stability and rotator cuff function, which shifts more stress onto the biceps long head tendon. It can also be exacerbated by a shoulder impingement (see next bullet).

- Shoulder Impingement (on Biceps Brachii Long Head Tendon): Subacromial impingement initially affects just the supraspinatus. It can worsen over time and end up impinging the biceps long head tendon and infraspinatus. This impingement occurs when a lack of scapular stability and poor rotator cuff function allow the humeral head to migrate up, pushing the tendons against the acromion and coracoacromial arch during arm elevation. Excessive use of overhead movements can also contribute to impingement since they fatigue the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff. When the biceps long head tendon is impinged, it can cause tendonitis and potentially contribute to tendinosis, partial- or full-thickness tears, or a complete rupture, among other biceps tendon issues.

Training Notes

- If you have tight/short biceps, do the following:

- Reduce the amount of direct biceps training in your routine.

- Stretch and release the biceps on a daily basis, including before and after workouts involving direct or indirect biceps training.

- Do more direct triceps training, since the triceps have likely become excessively lengthened and weak as a result of your overactive biceps.

- Avoid, or reduce the amount of time spent in, positions where the elbows are constantly flexed. When you have to be in these position for long periods of time (e.g. typing on a computer for work), extending your elbows or doing a quick biceps stretch every 15 or 20 minutes can make a difference.

- If you have biceps tendinosis, consider the following.

- See a doctor (preferably a sports medicine or orthopedic doc) to confirm the diagnosis, check for other related conditions and provide a personalized guidelines for recovery.

- Stop putting excessive/repetitive stress on the biceps tendon:

- Apply heat to the tendon for 10-20 minutes at a time, multiple times per day.

- If you just started experiencing tendinosis, there may (or may not) be inflammation for the first week or so. If this is the case, you can taking an NSAID (i.e. ibuprofen) 2-3 times a day and icing the area for 15-20 minutes every few hours, can help reduce pain and inflammation. However, once the inflammation goes away after a week or so, this treatment will be useless at best or harmful at worst.

- For distal biceps tendinosis:

- Stop all heavy biceps and back/pulling work. Start rehabbing with very light curls and rows for high reps. This should include a lot of eccentric work (e.g. for dumbbell curls, bringing the dumbbell to the top of the range of motion with assistance from your unaffected arm, then allowing the affected arm to slowly lower it).

- Do stretches and release techniques to relax the muscle and improve its tissue quality.

- Get an elbow sleeve to wear during your workouts. This will keep the joint warm and promote blood flow to the tendon, which is essential for recovery. Plus, it may help reduce pain.

- For proximal biceps tendinosis:

- Stop all heavy overhead/arm elevation exercises (e.g. shoulder press, front raise), horizontal push exercises (e.g. bench press, dips) or other exercises that may aggravate the tendon.

- Stop or reduce time spent doing overhead activities/sports (e.g. baseball).

- Perform light scapular stabilizer exercises for the lower traps, mid traps/rhomboids and serratus anterior.

- Do light rotator cuff strengthening exercises for the infraspinatus/teres minor (e.g. dumbbell lying external rotation) and the subscapularis (e.g. dumbbell prone internal rotation).

- Do dumbbell front raises using very light weight for high reps, with an emphasis on the eccentric rep (i.e. raising the dumbbell to the top of the range of motion with assistance from your unaffected arm, and allowing your affected arm to lower it).

- Gradually increase resistance over time for the above-mentioned exercises.

- Once the muscles become stronger, you may be able to add in some the overhead/arm elevation exercises and horizontal pressing exercises, obviously starting with light weight. To be safe, do shoulder-friendly variations wherever possible (e.g. replace barbell shoulder press with high incline neutral grip dumbbell press; replace bench press with neutral grip flat dumbbell press).

- Avoid dips altogether since they’re probably the most stressful movement for your proximal biceps tendon.

- Release and stretch the biceps, as well as the anterior deltoid, pec major, pec minor and lats. This will help relax these overactive muscles and encourage overhead movement that minimizes impingement. Also, do thoracic extensions on a foam roller if you have poor thoracic spine mobility. This encourages proper rib cage and scapula position, which allows for greater overhead range of motion with minimal impingement.

- Proximal biceps tendinosis is correlated with the classic hunched-over, forward head posture. If you have this type of posture, improving it can only help your tendinosis, even if only indirectly. See how to fix upper crossed syndrome (article coming soon) for more details on this.

- If you have a shoulder impingement affecting the biceps long head tendon, refer to the above bullet points regarding proximal biceps tendinosis. However, don’t do the dumbbell front raises rehab work, as this may aggravate the impinged tissues. Focus only on strengthening the scapular stabilizers and rotator cuff, and improving bad postural habits. Only return to weighted overhead and horizontal pressing exercises if you can do so without pain from impingement. Additionally, icing the tendon and taking NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen) can help if the impingement is causing inflammation.

- If you don’t have any biceps issues, but just want to build bigger biceps and improve exercise technique, consider these training tips:

- Don’t use momentum to curl the weight. Too many people butcher the form by jerking their torso back and driving their hips forward. This not only takes the focus off your biceps and increases injury risk, but makes you look like a buffoon. That said, a little bit of “controlled cheating” is sometimes necessary for progress if you’re an experienced lifter using heavy weights.

- Use full range of motion. Curl the weight up until you physically can’t flex your elbows any further – no half reps! Lower the weight until your elbows are straight. You don’t have to do a full bone-on-bone lockout, but if there’s a noticeable bend in your elbows at the bottom of the rep, you’re doing it wrong.

- Keep your shoulders back and down during curls. Don’t allow them to roll forward.

- Curl the weight up at relatively fast tempo (~1 second or slightly less). Squeeze at the top. Control the weight on the way down by lowering it at a slightly slower tempo than the positive rep (~1-2 seconds).

- Change it up between barbell and dumbbell curls. A barbell will allow you to lift the most weight, which is great for progressive overload since you can gain strength faster. However, if you only do barbell curls, these strength gains may eventually dry up because you’ll develop a strength imbalance between left and right biceps. Adding, or switching to, dumbbell curls will solve this problem.

- For the past year or so, I’ve only done had only one biceps exercise (which I did for several sets, twice a week) in my program at any given time. I’d do barbell curls for a few months until my progress became too slow, then I’d switch to dumbbells for another few months until my progress slowed again, and so on. The end result was a general uptrend in strength and (biceps size) over time.

- Don’t forget about other elbow flexors. The brachialis and brachioradialis, when developed, will make your arms look much thicker and fuller.

- Don’t neglect the triceps. After all, they make up two-thirds of the upper arm mass.

- See also my biceps training guide for more strategies, tips and other information relating to the biceps.

Related Muscles

- Brachialis

- Brachioradialis

- Coracobrachialis