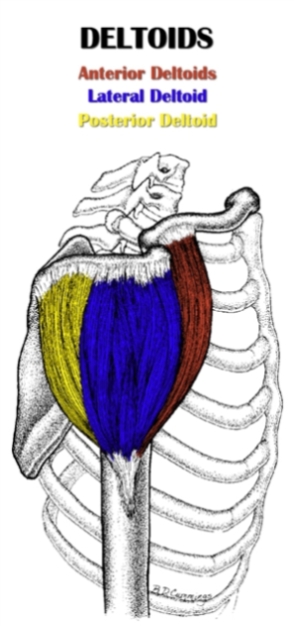

The lateral deltoid (L. latus, side ; deltoides, triangular) is the outermost head of the deltoid and is primarily responsible for performing shoulder abduction.

The lateral deltoid (L. latus, side ; deltoides, triangular) is the outermost head of the deltoid and is primarily responsible for performing shoulder abduction.

The lateral deltoid is part of the scapulohumeral (intrinsic shoulder) muscle group.

It is situated between the anterior and posterior deltoid, and lies superficial to the insertions of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor.

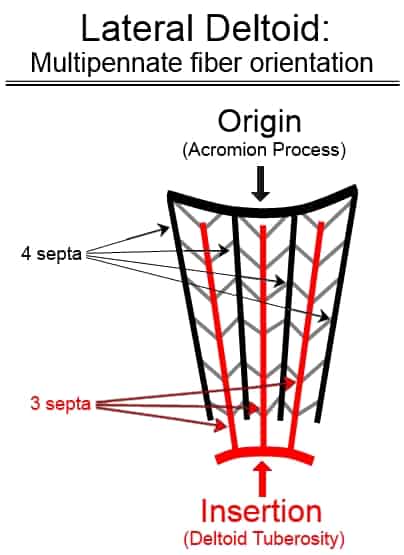

It originates from the acromion process on the scapula and inserts on the upper arm at the deltoid tuberosity.

There are four septa running down the muscle from its origin, and three septa running up from its insertion. The fibers run obliquely inward from the four septa toward the three septa, forming a multipennate fiber orientation.

The anterior and posterior fibers of the deltoid, in contrast, have a parallel fiber orientation.

Also Called

- Lateral delt

- Lateral head of the deltoid

- Medial deltoid (this is a misnomer – “medial” incorrectly describes the location of the muscle)

- Middle deltoid

- Outer deltoid

- Side deltoid

- Side of the shoulder

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Action | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Deltoid |

Superior surface of acromion process | Deltoid tuberosity of the lateral humerus |

|

Axillary nerve (C5-C6) |

Exercises:

Note: The table below only includes exercises that directly target the lateral head of the deltoid. However, it’s worth noting that the side delt gets an indirect training effect from most posterior deltoid exercises.

| Type | Name | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Barbell: |

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Dumbbell: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Cable: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Machine: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Bodyweight: |

Tutorial: N/A

|

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques:

Stretches

| Name | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

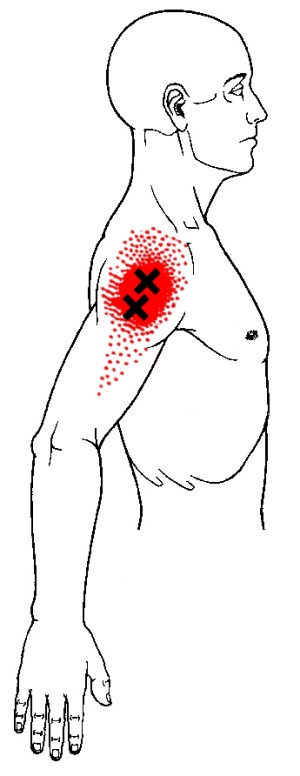

When using these techniques, give special attention to the common trigger points shown in the image below.

| Tool | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Common Issues:

- Inhibited/Lengthened Lateral Deltoid: The lateral delt becomes somewhat inhibited and lengthened in individuals that develop the postural distortion pattern known as upper crossed syndrome, or UCS. One of the postural changes that occurs from these imbalances is an increase in shoulder internal rotation and scapular protraction. When the shoulder is internally rotated, the lateral deltoid insertion is moved forward, thereby increasing the distance between origin and insertion, and putting the lateral deltoid in a chronically lengthened state. It is worth noting that this lengthening effect is relatively mild, but it’s nonetheless present. Additionally, shoulder internal rotation and scapular protraction during lateral deltoid exercises reduces lateral delt activation while increasing the activation of other muscles (e.g. upper trap, supraspinatus, anterior delt or posterior delt, depending on the exercise). UCS is often caused by repetitive activities such as excessive upper body push exercises and hunching over for long periods of time.

Training Notes:

- If your lateral delts are inhibited and lengthened, then consider the following suggestions.

- Increase training volume or frequency on lateral deltoid exercises.

- Increase training volume or frequency on exercises that train the often-weak mid back/scapular stabilizers (i.e. do more lower trapezius exercises, middle trapezius/rhomboids exercises and serratus anterior exercises).

- Decrease training volume or frequency on chest and front delt exercises. Also, avoid shrug variations (overhead shrugs are okay) to minimize upper trapezius and neck muscle activation.

- Do soft tissue release techniques and stretches for the pec major and pec minor, front delt and upper trapezius. These muscles are most likely play the biggest roles when it comes to overpowering the lateral deltoid.

- You may need to avoid, or at least be careful with, front delt and chest stretches if you have any shoulder joint issues (e.g. anterior humeral glide), since these stretches put the arm in a position that could could potentially aggravate a vulnerable shoulder.

- Even though your lateral deltoid may be somewhat lengthened or inhibited, it could also be full of trigger points and soft tissue adhesions that are impairing its function. As such, you should try also use release techniques on your lateral delt (see above), but do not stretch it. When I first tried rolling a lacrosse ball on the lateral delt against the wall, I immediately found some major trigger points. When I put enough pressure at the right point, I could literally feel the muscle release because the muscle was twitching/fluttering and tension quickly dissipated (an awesome feeling!).

- You should also try releasing (but not stretching) the rear deltoid. It is similar to lateral deltoid in that it often inhibited/lengthened, but nonetheless a common area for trigger points to develop.

- Avoid bad postures that contribute to the inhibition/lengthening of the lateral delt. This means stop staying in positions where you’re hunched over for long periods of time (e.g. typing on computer, using smarthphone, playing video games). Keep your torso straight and your shoulder blades back and down. And if you do find yourself assuming a bad posture for a long time, just take a quick break to get out of that position; stand up, stretch or move around, even if it’s just for a few seconds.

- Following the advice in the above bullet points should get you well on your way to correcting your inhibited/lengthened lateral deltoid. However, assuming upper crossed syndrome (UCS) is the root cause of your dysfunctional lateral deltoid head, you need to correct UCS with a comprehensive strategy if you want to permanently fix your lateral delt imbalance (which in most cases will be a very minor issue compared to the other muscular dysfunctions/imbalances caused by UCS). Please refer to my guide on this subject: how to fix upper crossed syndrome (article coming soon).

- Below, I’ll share training advice and technique tips to ensure you’re actually working the lateral delts properly. Plus, I’ll fill you in on some non-training factors that may be preventing you from having that highly-developed lateral delt look. All of this knowledge will help you achieve wider and more capped shoulders, faster.

- If you want to fully develop your lateral deltoids, then you’re going to have to hit them directly. Contrary to what some might tell you, major compound shoulder movements like the overhead press don’t provide nearly enough stimulation for muscle growth in the lateral delts. You only need one lateral deltoid exercise to work the muscle sufficiently, so try several and stick with the one that allows you to feel muscle contracting most intensely. For most people, this will be the dumbbell lateral raise or one of its many variations.

- Train the lateral delts frequently (i.e. 2-3 times per week). Your goal should not be to destroy them each time. Rather, do just 3-5 sets each workout. Although this is relatively low volume per workout, it is high volume per week. Each workout will provide enough volume to stimulate growth, while also allowing sufficient recovery to stimulate growth a second or third time during week.

- The lateral deltoid has about the same amount of fast twitch muscle fibers as it does slow twitch muscle fibers (to be precise, it is slightly slow-twitch dominant). As such, it is likely best-suited for moderate to lighter weight with a moderate to higher rep range (i.e. 6-15). However, I personally don’t like using weight that I can’t do for at least 8 reps, since the heavier the weight, the more form breaks down; obviously this is true for any exercise, but it is especially true for lateral delt exercises since even a small deviation from proper range of motion and arm positioning can completely remove the tension from the muscle.

- Don’t forget to do posterior deltoid exercises as well. The lateral delt is the most important part of the deltoid for shoulder aesthetics from both the front and rear view. However, the posterior delt is most important part from the side view. And even though it gets worked somewhat in back exercises, that often isn’t enough for sufficient development. As for the anterior deltoid, it has a relatively minor aesthetic role and doesn’t need to be isolated since it gets more than enough work from bench press and overhead press.

- Trigger points are common in not just the lateral deltoid, but the entire deltoid muscle. Therefore, doing soft tissue release on each deltoid head is important for maintaining mobility through the main shoulder movements (i.e. lateral head = abduction, anterior head = flexion, posterior head = extension) and preventing imbalances between the three heads. I find that using a lacrosse ball against the wall works best for both the lateral and anterior heads, whereas a lacrosse ball against the floor is most effective for the posterior head. See lateral, anterior and posterior head release techniques.

- If you have certain shoulder issues, then you might have to avoid some lateral deltoid exercises, either because they’re unsafe or just ineffective. For example, if you’re prone to shoulder impingement issues, then it’s a good idea to stay away from upright rows. To give you a personal example, I had/have poor scapular stability on my left side. Until I was able to improve this issue, I could never feel my left lateral delt working during dumbbell lateral raises. This was because having the dumbbells so far away from my center made it impossible to maintain proper position and movement of my shoulder blade, which in turn messed up my arm position and movement. I stopped doing this movement, and found success with exercises that keep the weight closer to the center of the body; specifically, the machine lateral raise (with upper arm pads) and the dumbbell raise worked best.

- Your posture can make or break your how muscular your lateral deltoids appear. If you have the classic hunched posture with your shoulder rolled forward, then the muscularity of your lateral deltoids will be hidden. This is because your shoulders are internally rotated, which moves the lateral deltoids away from the side and toward the front. Also, when the shoulder blades are protracted forward, the overall shoulder-to-shoulder width of your body is narrowed. Fix this by pulling your shoulder blades back and externally rotating your shoulders to neutral (i.e. with hands at side, thumbs should point forward). The difference will be night and day, and like me, you might be surprised to find out you actually have some decent lateral delt development after all. Don’t believe, stand in front of the mirror and observe how your delts look with bad posture, then with good posture.

- Genetics play a big role in the shape and size of all muscles. However, their role in the aesthetic potential of some muscles is much more profound than in other muscles. Unfortunately (or fortunately if you are genetically blessed), the lateral deltoids, much like the calves, are one of those muscles. Basically, good shoulder genetics are a prerequisite to having deltoids that actually stand out. Even if you have average shoulder genetics and train the lateral delts with optimal volume/frequency/intensity, the best you can achieve is outer deltoids that don’t look bad (i.e. they won’t look like they’re lagging, but they’ll never be a strong point). This is different than many other muscles (e.g. biceps, triceps, quads, lats), which despite being genetically average, can be developed into strong points, given enough time and the right training.

- What determines good genetics for the lateral deltoid? By far the most important component is having a wide shoulder girdle, which essentially means having long collar bones. The longer your collar bones are, the broader your shoulders will be, and the more pronounced the overlying muscle will appear. Surely, there are other factors play that play a role in good lateral delt genetics, but I couldn’t say for sure what those things would be – I can, however, speculate as to what these factors might be related to. For example, one factor could be a naturally higher androgen receptor density in the deltoids, which equates greater muscle growth potential. Also, certain deviations in the locations of the acromion process (origin attachment) and the deltoid tuberosity (insertion attachment) might create a rounder outer deltoid shape.

Very good explanation….

Ive been doing weights for 40yrs & yor the 1st person to actualy relay the complex understanding of what the side delt actualy does…..

Good work mate…?

Thanks Erwin!

Very informative! I have been lifting on and off for the past decade(injuries sidelined me for quite a while) and so i am relatively fit with a good degree of muscle development. That being side, my lateral deltoids dont even seem to attach to my shoulder and have large gaps between them. The anterior and posterior are well developed but it looks like the medial delt space is virtually empty. What causes this? It doesnt seem to be congenital as the men in my family(even those that are unfit) seem to have a natural roundness

I’d have to see a photo to get a better idea of your situation. That said, I would’ve said it might be congenital in terms of some odd attachment point; though you seem to think it’s not. The other main possibility I can think of is just lack of development. Some times you really need to work hard to get enough mass on the side delts to see a visual difference.