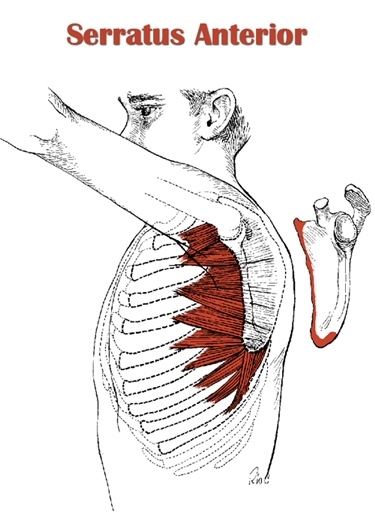

The serratus anterior (L. serratus, saw ; anterior, front.), named for its saw-like appearance, is located on the side of the ribcage.

It acts on the scapula and is the prime mover in both scapular protraction and scapular upward rotation.

It’s also a key scapular stabilizer, keeping the shoulder blades against the ribcage when at rest and during movement.

Classified as an anterior axioappendicular muscle, the majority of the muscle lies deep to the scapula, subscapularis and parts of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi.

The anterior part of the lower fibers are visible on the physique at low body fat percentages.

The serratus anterior arises from the top nine ribs and wraps posteromedially around the ribcage, passing beneath the scapula. It inserts on the underside of the scapula on its medial border.

As the muscle extends from the ribs, it is divided by tendinous septa into nine finger-like groupings of muscle fibers called “digitations.”

The fibers run obliquely (to varying degrees) between these septa, forming a multipennate muscle architecture.

The upper three digitations are considered the superior fibers while the lower six digitations are considered the inferior fibers.

Fun Fact: The lowest four digitations of the serratus anterior interdigitate with the fibers of the external oblique, creating an aesthetic “tie-in” area that can be observed at a low body fat.

Table of Contents

Also Called

- SA

- Serratus

- Serratus magnus

- Boxer’s muscle

- Big swing muscle

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Superior Fibers | Inferior Fibers |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | External surface of ribs 1-3 | External surface of ribs 4-9 |

| Insertion | Anterior surface of the medial border of the scapula | Anterior surface of the medial border of the scapula |

| Action | Scapular protraction |

|

| Nerve Supply | Long thoracic nerve (C5-C7) | Long thoracic nerve (C5-C7) |

Exercises:

Note: The table below only includes the exercises that most directly target the serratus anterior.

The serratus anterior is trained indirectly in all anterior deltoid exercises. It is also hit to some extent in the select few chest exercises that involve scapular protraction (i.e. clap push up or similar variations).

Barbell Exercises:

- Incline shoulder raise

- Flat shoulder raise

- Overhead shrug

Dumbbell Exercises:

- Incline shoulder raise

- Flat shoulder raise

- Overhead shrug

Cable Exercises:

- Incline shoulder raise

- One arm incline push

Machine Exercises:

- Incline shoulder raise

- Flat shoulder raise

Bodyweight Exercises:

- Scap push up (aka push up plus)

- Scap push up on forearms

- Scapular wall slide

- Forearm wall slide

Isometric Exercises:

- Plank (emphasizing protraction)

- Straight arm plank (emphasizing protraction)

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques:

Stretches

- Serratus anterior wall stretch

- Serratus anterior arm-behind-back stretch

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

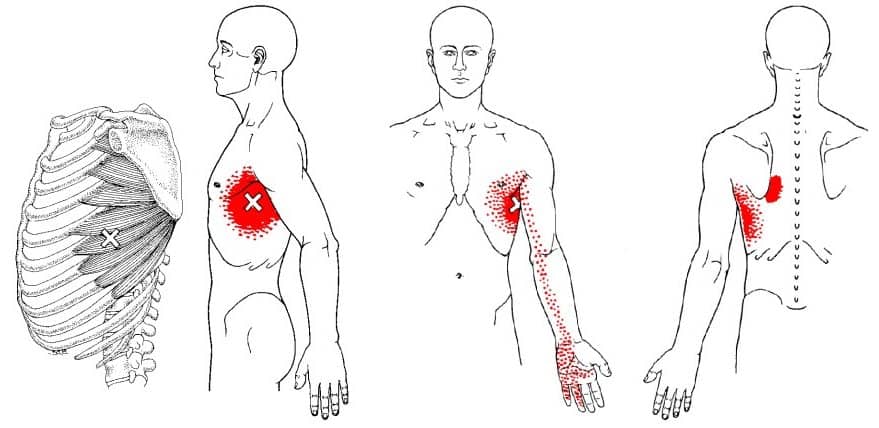

When using these techniques, give special attention to the trigger point shown in the image below.

Tool

- Lacrosse ball

- Backnobber II

- Foam roller

Common Issues:

- Inhibited/Lengthened Serratus Anterior: When the serratus anterior becomes inhibited and lengthened, scapular protraction and scapular upward rotation are impaired. This limits overhead range of motion and reduces overall scapular/shoulder stability, which greatly increases the risk of injury to the rotator cuff and shoulder girdle. If the serratus anterior becomes inhibited/lengthened enough, scapular winging can occur due to the inability of the serratus anterior to hold the scapula against the ribcage. This amplifies the aforementioned issues regarding shoulder mobility, stability and injury risk. The serratus anterior can become inhibited for a number of reasons – I’ll explain the most common ones below:

- Upper Crossed Syndrome (UCS): In UCS, the pec minor is overactive and short, which lends itself to scapular anterior tilt and scapular downward rotation. This inhibits and lengthens the serratus anterior, since it is responsible for the opposite actions: scapular posterior tilt and scapular upward rotation.

- Rhomboid Dominance: This occurs from doing a disproportionate amount of exercises involving scapular retraction (and/or downward rotation), causing the rhomboids to become overactive and short, putting your shoulder blades in a retracted and downwardly rotated position. This places the serratus anterior in a chronically stretched out and inhibited state since it is a scapular protractor and upward rotator.

- Nerve Damage: Damage to the long thoracic nerve can weaken, or even paralyze, the serratus anterior. Neurogenic scapular winging (i.e. scapular winging caused by nerve damage) requires treatment from an orthopedic doctor. In most cases, a non-operative treatment allows the nerve to heal, given enough time. But surgery is necessary in some cases. Only a doctor can verify if your case of scapular winging is neurogenic.

- Note: If your scapular winging is not severe and developed over time, chances are the cause is weakness from a muscular imbalance. This is a good thing, since it can be treated more easily, by using corrective exercise and improving posture.

Training Notes:

- If you have inhibited/lengthened serratus anterior, consider the following:

- Strengthen the serratus anterior with really easy, low-load exercises that allow you just feel the muscle working. I recommend forearm wall slides, incline push ups (or even push ups against a wall) and incline shoulder raises with very light weight. Gradually work towards more difficult variations and heavier loads.

- If your serratus anterior weakness is due to rhomboid dominance, consider the following:

- Decrease your training volume on rhomboids exercises (i.e. row and pull up variations).

- Release and stretch your rhomboids on a daily basis, and always after training them.

- Let your scapulae go to the end of the protraction range of motion, when lowering the weight on rows. This doesn’t mean to completely relax your upper back, as this can pull your scapulae beyond the normal protraction range of motion, which is dangerous.

- If you have dominant rhomboids, you can bet your serratus anterior won’t be the only “victim.” They’ll likely also inhibit the lower trapezius. Therefore, it’s a good idea to increase volume on lower trapezius exercises as well. One great movement to target this muscle is the prone Y. Or, if you want to kill two birds with one stone, the overhead shrug will train the lower traps and the serratus anterior at the same time.

- If your serratus anterior weakness is due to pectoralis minor overactivity associated with Upper Crossed Syndrome, consider the following:

- Release and stretch the pectoralis minor. This can help to calm down the overactive pec minor and allow the serratus anterior to activate and posterior tilt the scapula during upward rotation. If weak rhomboids/middle trapezius is also a problem for you, stretching and massaging the pec minor right before before training these muscles will allow you to activate them more effectively (i.e. you’ll have better form and range of motion during scapular retraction).

- Do more volume on rhomboid/middle traps exercises involving scapular retraction (i.e. row variations).

- See how to fix upper crossed syndrome (article coming soon) for a complete guide on fixing this postural distortion syndrome.

- If nerve damage is causing serratus anterior weakness, you need to consult with your doctor for a proper treatment protocol.

- Here are a couple technique tips for serratus anterior exercises:

- This goes for all serratus anterior exercises: “Glide” the scapula along the rib cage throughout the movement (i.e. the scapula shouldn’t lift off the ribs at any point). This requires constant activation of the serratus anterior to stabilize and move the scapula. If you can’t keep your scapulae from lifting off the rib cage, that’s a good indication that you need to reduce the weight or do an easier variation of the exercise.

- For scap push ups, you must engage your core to keep your body straight. Maintain a neutral spine; don’t let your hips sag, and keep your chin retracted. All of this is allows you to achieve and maintain good thoracic spine position, which is necessary for proper movement of the scapulae.

- Some people seem to think the bench press and its many variations involve scapular protraction. So, I feel it’s necessary to point out that this is not the case. Sure, the bench press does resemble scapular protraction exercises in terms of arm movement. But the distinction is that the scapulae stay down (scapular depression) and back (scapular retraction) during the bench press. In this way, the bench press can actually contribute to serratus anterior weakness (if you have rhomboid dominance, as discussed earlier).

It would be helpful if you posted pictures/videos of the exercises and stretches you describe.

Thanks for the comment, Chris. I totally agree! It’s definitely on my to-do list for ALL the anatomy pages. I don’t have a set timeline for when it will be finished, but I have begun taking photos for the different exercises, stretches and mobility techniques on a few of the muscle group pages.

I believe I suffer from seratus anterior inhibition but also over active rectus abdominus/under active transverse abdominus resulting in a blocky core with over developed obliques. Which is the root of the entire issue? The abdominus or the seratus anterior? Diaphragm control has been an issue as well, a symptom of upper cross.

Hard to say from my end. I’d definitely ask a good sports physiotherapist who can give you an analysis. However, in my experience and hearing from lots of others, it almost always helps to try to focus on the underdeveloped muscles and bringing them up to bar, which in turn can balance out the overactive ones. In this case, I think that would start with the serratus anterior. And probably also the lower traps, which work in conjunction with them on many scapular motions.