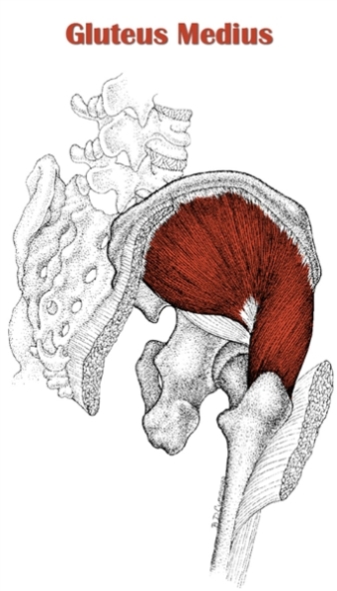

The gluteus medius (G. gloutos, buttock. L. medius, middle) is the second largest of the three gluteal, or butt, muscles.

It is a fan-shaped muscle, whose main action is hip abduction. It is also noted for its essential role as a hip stabilizer in the gait cycle.

The gluteus medius is classified as part of the superficial gluteal region.

It lies deep to the gluteus maximus and superficial to the gluteus minimus.

Only the anterosuperior 1/3 of the muscle is left uncovered by the gluteus maximus, though that portion is actually deep to the gluteal aponeurosis, making the gluteus medius virtually hidden from the surface of the body even at low body fat percentages.

From a broad origin on the external surface of the ilium, the parallel-oriented gluteus medius fibers run inferomedially from either end of the muscle relative to its midline.

The fibers converge as they insert on the lateral greater trochanter, giving the gluteus medius its fan-like, or radiate muscle shape.

Note: Although most sources agree that the gluteus medius is a radiate muscle with a parallel fiber orientation, some sources class it as a multipennate muscle.

Also Called

- Glute med

- Hips

- Hip abductor

- The walking muscle (this term is sometimes also used for the psoas)

- Deltoid of the hip

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Action | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gluteus Medius | Dorsal surface of the ilium between anterior and posterior gluteal lines | Lateral surface of the greater trochanter of the femur |

|

Superior gluteal nerve (L5-S1) |

Exercises:

Note: The table below only includes exercises that work the gluteus medius directly, meaning movements that feature the action of hip abduction or internal rotation. These are the same exercises that train the gluteus minimus directly.

The gluteus medius is worked significantly as a stabilizer via isometric contraction in any standing or lying single leg exercises for the gluteus maximus, quadriceps or hamstrings (e.g. single leg RDL, barbell step up, Bulgarian split squat, single leg glute bridge).

| Type | Name | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Dumbbell: |

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Cable: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Machine: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Other: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Weighted: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Bodyweight: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Isometric: |

Tutorial: N/A

|

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques:

Stretches

Note: These are the same stretches used for stretching the gluteus minimus.

| Name | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

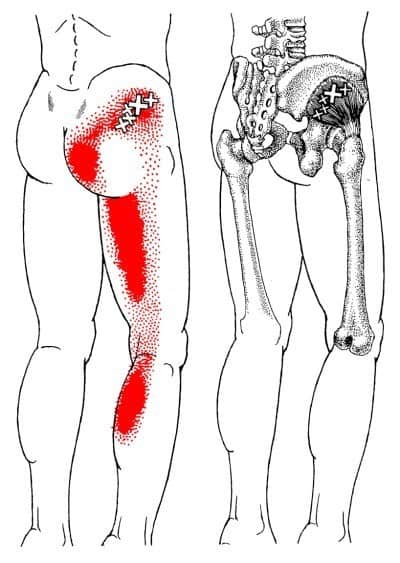

When using these techniques, give special attention to the common trigger points shown in the image below.

| Tool | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Common Issues:

- Inhibited/Excessively Lengthened Gluteus Medius: The gluteus medius is typically weak and lengthened in those with the postural distortion pattern known as lower crossed syndrome (LCS). One of the imbalances that occurs in LCS is tight hip flexors. This becomes a problem for the gluteus medius when one particular hip flexor becomes tight, namely the tensor fascia lata (TFL). The TFL, like the gluteus medius, also contributes to hip abduction and hip internal rotation. As such, the TFL can become synergistically dominant over the gluteus medius and inhibit it in these hip movements. The piriformis can also inhibit the gluteus medius: As a hip external rotator (or internal rotator if hips are flexed beyond 90°) and hip abductor that can become overactive to compensate for gluteus maximus weakness, the piriformis will reciprocally inhibit the gluteus medius during internal rotation and synergistically inhibit it during abduction. Finally, the hip adductors also tend to become overactive/short in LCS and reciprocally inhibit the gluteus medius. The aforementioned muscular imbalances contribute to externally rotated hips with range of motion and strength losses in hip abduction and hip internal rotation (or hip external rotation if hips are flexed beyond 90°). Gluteus medius weakness is commonly a cause of the following:

- Knee pain/injury: If it can’t perform its role as a hip abductor, your knee won’t be able to track over your foot when walking/running, or during any single leg movement or bilateral movements such as squatting. Your knees to collapse inward, which puts valgus stress on the knee. This collapse occurs because the thighs adduct. And if your hips are flexed (e.g. at bottom of a squat), the thighs will also internally rotate. If your TFL is overactive, the IT band will be excessively tight, further increasing valgus stress.

- Ankle pain/injury: Gluteus medius weakness can contribute to excessively pronated feet. If the gluteus medius is unable to abduct sufficiently to resist overactive/short adductors, the ankle will pronate, or collapse inward. Pronation is made worse if the hip external rotator muscles are also weak; this allows the thigh to rotate internally, which encourages internal rotation of the knee and lower leg, and causes more severe pronation. See pronation distortion syndrome (article coming soon) for more on this.

- Lower back pain/injury: Since the gluteus medius functions to keep the pelvis even when walking/running and during single leg movements, weakness of this muscle equates to poor hip and pelvic stability. This increases the likelihood of lower back injury, since the spine is not supported by a stable structure. Furthermore, the body may try to compensate with the contralateral quadratus lumborum to keep the hips level, thereby creating an muscular imbalance affecting the lower spine that could eventually lead to pain and injury.

Training Notes:

- If you have a weak/excessively lengthened gluteus medius, do the following:

- Do soft tissue release techniques and stretches for the muscles that commonly inhibit the gluteus medius, namely the TFL, piriformis and hip adductors.

- Perform basic, low resistance activation exercises for the gluteus medius. It’s essential that you “turn off” the overactive muscles by doing release techniques and stretches immediately before doing activation work (see previous bullet point). As far as exercise choice goes, it’s important to choose exercises that maximize gluteus medius activation while minimizing involvement of the overactive synergists. I recommend starting with the band clam shell and side lying hip abduction, using no resistance. When ready, start using light resistance, gradually increasing it over time. Eventually, progress to more advanced exercises like side bridge holds and lateral band walks, gradually increasing resistance or time under tension as you get stronger.

- Once you’ve achieved a decent level of gluteus medius strength from basic activation work, it’s time to increase training volume. You can do this by adding new exercises, some of which should be more direct gluteus medius exercises. But you should add at least one exercise that lets work the gluteus medius intensely as a stabilizer in a compound/full body movement rather than as a prime mover in an isolated movement. This allows you to train the muscle in the context of a “functional” movement. The single leg squat or single leg RDL are both a great example of such an exercise.

- Gluteus medius inhibition can negatively impact your form on almost any other lower body exercise. Typically, this presents as the knees/thighs caving in at the bottom of the movement. Even if your gluteus medius becomes strong enough from activation exercises, you may still have faulty movement patterns from learning and repeating the incorrect movement. As such, you need to focus on improving motor control by pushing your thighs outward on all lower body exercises to fix your technique. Reduce the weight so that you can effectively ingrain the proper movement pattern.

- Buy some mini-bands. These are cheap, but very useful tools that can be used to improve gluteus medius motor control/reinforce proper technique on any squat variation while also strengthening the muscle. You loop the mini-band around your lower thighs, just above the knees. Then proceed to do squats or any two-legged squat variation/alternative; focus on resisting the band by keeping your thighs abducted and externally rotated, especially near the bottom of the range of motion.

- Avoid direct hip flexor exercises (e.g. knee or leg raises).

- Avoid hip adductor exercises involving the actual movement of hip adduction (e.g. cable hip adduction, swiss ball thigh squeeze). Also, avoid or reduce training volume on hip adductor exercises that involve using a wide stance (e.g. sumo deadlift/squat) or stepping to the side or at an angle (e.g. side step up, side lunge, angled lunge). All other hip adductor exercises (e.g. lunge, step up, split squat) are okay since they train the abductors and adductors equally.

- Try to avoid postures or activities that cause the gluteus medius to become inhibited. This means spending less time sitting down. If you have to sit for long periods of time for your job or at school, make it a habit to take a brief break to walk around or at least stand up a couple times per hour. Another position to avoid being in for too long is leaning your hips to one side in such a way that you’re stretching your gluteus medius. This is something you might do if you work at a job where you must stand behind a desk for long periods of time (e.g. cashier, front desk attendant).

- The points above provide an initial strategy for addressing gluteus medius inhibition. However, this problem is often just one symptom of a larger problem: pronation distortion syndrome or lower crossed syndrome. If you’re affected by one of these postural distortion patterns, you must address it in its totality for a complete and long-term fix. Please refer to how to fix lower crossed syndrome and how to fix pronation distortion syndrome (articles coming soon).

- The following is general advice and tips for gluteus medius training. It is mostly directed at trainees with more or less properly functioning glute med muscles, though some advice may also help those with dysfunction:

- To strengthen the muscle, integrate direct gluteus medius exercises into your routine.

- Do a couple light sets as part of your warm up before lower body training. This will get the glute med firing so it can do its job correctly on heavy squats and deads.

- Do a few sets with heavier resistance near the end of your workouts, after completing all your main lifts. Use light-moderate weight for moderate-high reps (e.g. 8-15+ reps per set). Do these exercises 1-2 times per week.

- Maintain a neutral pelvis when performing all gluteus medius exercises. It’s common to have anterior pelvic tilt, which inhibits your gluteus medius and causes you to compensate with the piriformis, TFL or quadratus lumborum (depending on the exercise). So, keep your abs and gluteus maximus tensed to maintain the neutral position.

- Proper form is essential on gluteus medius isolation exercises, since even minor flaws can shift the focus to the wrong muscle. Often, the biggest challenge is to minimize involvement of the TFL. I’ll give cues for minimizing TFL involvement on some of the most popular exercises:

- Clam shell: Keep the shin of the involved leg internally rotated, such that the foot is pointed slightly down throughout the movement.

- Side lying hip abduction: Keep the involved thigh at neutral rotation throughout the movement; do not externally rotate it as this will make the exercise into more of a hip flexion movement. Also, if you’re strong enough, you can increase the efficacy of the movement by extending the thigh past neutral, into extension.

- Don’t forget to work gluteus maximus, too – you can never really get your glutes too strong! And if you want to train the gluteus maximus and medius at the same time, you simply can’t beat standing/lying single leg exercises like the single leg deadlift, single leg squat or single leg glute bridge.

- To strengthen the muscle, integrate direct gluteus medius exercises into your routine.

Dear King of the Gym (your majesty),

Excellent content! Question: I sometimes get lower back spasms during/after barbell back squats. Could it be due to weak (or imbalanced) glute medius?

Also, might simply standing on one leg help to strengthen the glute medius?

Thanks for your thoughts!

Yon

Haha thanks, Yon. I kind of like the ring of “Your Majesty” 😀

It’s impossible for me to say whether or not your glute med is responsible for the back spasms you experience. You’d have to go to a physician or physical therapist for a proper diagnosis.

However, glute med dysfunction is certainly associated with back pain–See these studies:

While we don’t know if the glute med is causing these issues, chances are you could still benefit from strengthening it–most people could use stronger gluteus medius muscles. And, hey, it may very well improve your spasms/low back pain.

Standing on one leg can help, assuming you’re actually activating the glute med, as opposed to just leaning into it and stretching it. To help you better visualize what I’m describing here, see artistic rendition below:

However, the standing on one leg thing is something you can do almost passively throughout the day. In addition to that, though, I would recommend adding in one actual gluteus medius movement…

…My favorite is the single leg Romanian deadlift (RDL). Start with 3 sets x 10-15 reps for each side, 2-3 times per week.

When you do single leg RLDs, you also need to focus on keeping the glute med active (and not leaning into the hip as shown above) throughout the movement. It helps me to look in the mirror to make sure I’m staying in the right position.

At first, this it’s going to be a challenge to simply stay balanced. So, you can hold onto a something (e.g. a railing, a bar, a power rack post or whatever) keep yourself from falling over. Eventually, you’ll be able to do the movement without any assistance.

Once you can do 10+ reps with bodyweight and not holding onto anything, you can progressively add weight. Start by holding a 5 lb dumbbell in one hand; hold on the same side as the leg that’s elevated. Then, continue to progressively add weight over time as you get stronger.

All the best,

Alex

I have an irregular trochanter tendon which causes severe pain in the hip….please help