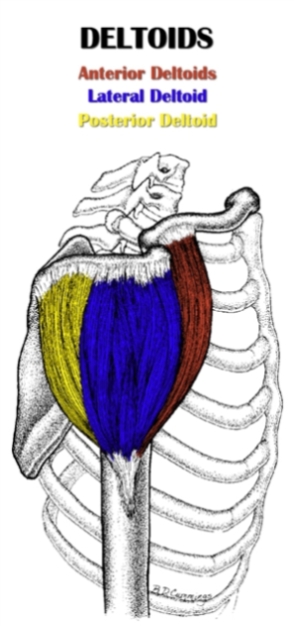

It acts on the shoulder joint and is the prime mover in shoulder horizontal abduction.

Located on the back of the shoulder – medial to the lateral deltoid and lateral to the middle trapezius – the posterior deltoid is classified as a scapulohumeral (intrinsic shoulder) muscle.

As part of the outermost layer of muscle, the posterior deltoid lies superficial to portions of the infraspinatus, teres minor and teres major.

It originates from the scapular spine and inserts on the upper arm at the deltoid tuberosity.

The posterior deltoid fibers have a parallel orientation and run inferiorly from origin to insertion.

Also Called

- Posterior delt

- Posterior (or rear) head of the deltoid

- Rear deltoid

- Back of the shoulder

Origin, Insertion, Action & Nerve Supply

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Action | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior Deltoid |

Inferior border of the spine of the scapula | Deltoid tuberosity of the lateral humerus |

|

Axillary nerve (C5-C6) |

Exercises:

Note: All exercises listed below target the posterior deltoid directly. However, there are other movements that train the rear delt indirectly, including row variations (see rhomboid exercises for specific examples) and lat exercises involving vertical pulling (e.g. pull up, lat pulldown)

| Type | Name | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Barbell: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Dumbbell: |

Tutorial: Bent over rear lateral raise

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Cable: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: Face pull

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Machine: |

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

|

| Weighted: |

Tutorial: Inverted row

|

|

| Bodyweight: |

Tutorial: Inverted row

|

Stretches & Myofascial Release Techniques:

Stretches

| Name | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Self Myofascial Release Techniques

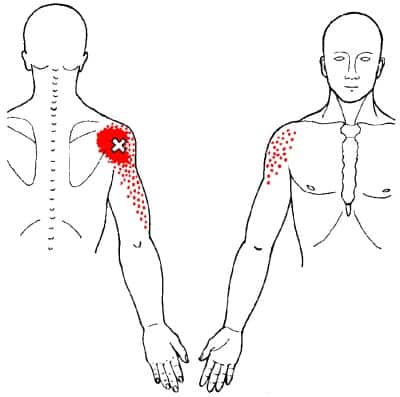

When using these techniques, give special attention to the trigger point shown in the image below.

| Tool | Picture |

|---|---|

Tutorial: N/A

Tutorial: N/A

|

Common Issues:

- Inhibited/Lengthened Posterior Deltoid: The rear delt is inhibited and lengthened in people with upper crossed syndrome (UCS). In UCS, the shoulders are internally rotated because the pec major and anterior deltoid are overactive and short. The constant pull of these tight muscles stretches the scapular retractors and posterior deltoids into a chronically lengthened position, which inhibits their function. When the rear delt is inhibited, it becomes harder to activate it during compound pull movements, which causes other muscles (e.g. biceps, lower spinal erectors, lats) to compensate for it. This further increases the imbalance between the pecs/anterior deltoid and rear deltoid, which will eventually lead to issues with the actual shoulder joint. Upper crossed syndrome – specifically the aspect of internally rotated shoulders – is brought on by poor postural habits (i.e. hunching over with shoulders forward and rotated internally), as well as an excessive focus on push exercises (e.g. bench press, overhead press) and vertical pull exercises (e.g. pull up, lat pulldown) combined with an inadequate focus on horizontal pull exercises (e.g. barbell rows, any direct rear delt exercise) and external rotation exercises (e.g. face pull with external rotation, prone cobra).

Training Notes:

- If you have inhibited and excessively lengthened posterior deltoids, then the advice listed below may be of use to you.

- Increase training volume or frequency on posterior delt exercises. I highly recommend doing the face pull with external rotation, since it hits the rear delt hard, while also training the often-weak lower/mid traps, rhomboids and infraspinatus/teres minor. In addition to the face pull, I recommend doing one more rear delt exercise of your choice that focuses solely on rear delt activation (i.e. any rear delt row or rear delt lateral raise variations).

- Increase training volume or frequency on compound horizontal pull exercises that target the back (e.g. barbell row, one arm dumbbell row, seated cable row). These movements provide some indirect rear delt activation. More importantly, they train the scapular retractors and the thoracic spinal erectors, which typically contribute to rear deltoid dysfunction because they are also weak.

- Cut down on training volume or frequency of chest exercises and front deltoid exercises.

- Release and stretch the chest (pec major and pec minor) and front deltoid. If you have shoulder joint issues, be careful with these stretches, since they put your arms in positions that can easily irritate the shoulder joint if it already has poor stability.

- Despite its tendency toward being inhibited/lengthened, the rear deltoid is often a hot spot for trigger points. This may be due to the fact that it must constantly resist the pull from a tight pec major and front delt. Other times, the rear deltoid may actually be overactive (but still lengthened) because it compensates for a lack of scapular retraction with shoulder hyperextension. Whatever the case, you should work these trigger points out with rear delt release techniques (my favorite technique is lying on my side with a lacrosse ball between my rear delt and the floor). This works wonders for improving overall shoulder mobility and function. Accordingly, you should do it as part of your warm up for any upper body training, especially before working the rear delts (duh!) and any pull exercises.

- Assuming your rear delt is excessively lengthened, avoid stretching it.

- If your rear delt has knots in it, chances are your lateral deltoid does too. As such, performing lateral delt release techniques is recommended (my go-to technique is massaging it with a lacrosse ball against the wall). However, don’t stretch the lateral deltoid, since it’s often excessively lengthened.

- If you’re constantly hunching over, you’ll never fix your imbalance because this type of posture puts the rear deltoid is in a chronically stretched position. It needs to shorten to return to its normal resting length so that it can function properly. You can facilitate this by avoiding bad postures throughout the day. Stand and sit up straight, keeping your shoulders back and down with your abs/obliques engaged. Your posture doesn’t have to be perfect all the time. The most important things are: changing your body position often to break up the amount of time spent in bad postures, and reduce the total amount of time you spend in bad postures.

- The above bullet points provide more than enough information to get you on the right track for fixing your rear deltoid imbalance. That said, if upper crossed syndrome (UCS) is the underlying problem, then you must also address it. This way, you can fully and permanently correct your rear delt dysfunction as well as any other imbalances caused by UCS. Please refer to how to correct upper crossed syndrome (article coming soon).

- Use the following pieces of training advice to develop the posterior head of your deltoid, faster.

- If you want to achieve significant growth, it’s essential that you use isolation rear delt exercises to target the muscle directly. You can’t get it anywhere near its full potential by relying solely on compound back exercises. In fact, chances are your posterior delts will actually become underdeveloped if they don’t receive any direct attention, which can eventually lead to shoulder and postural problems as well as reduced performance on upper body pull and push exercises. Test out several direct posterior deltoid exercises and find the one that allows you to really feel the rear delt activating. Stick with just that one exercise and do it 2-3 times per week for about 3-5 sets per session. You’re only trying to work them hard enough to stimulate growth, but not so hard that they can’t recover before working them 1-2 more times during the week. Progressively increase the weight, but do so slowly – you don’t want to sacrifice proper form and get poor muscle activation (it’s very easy rear deltoid exercises to use momentum or rely on other muscles to perform the movement).

- The ratio of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in the posterior deltoid is about half and half (with a slightly higher proportion of slow twitch fibers). As such, moderate to high repetitions (6-15) tend to be better for stimulating growth. I recommend staying towards the higher end of that rep range because it ensures the weight is light enough that you can maintain proper form and keep tension on the rear delt.

- Don’t forget to target the lateral deltoids, too. While well-developed rear delts makes an important contribution to visual impact of the shoulders, the lateral delts are by far the most important part of the deltoid when it comes to improving overall aesthetics. They add directly to the width of your upper body and give your shoulders a “capped” appearance.

- Even if you have no major imbalance or dysfunction of your posterior deltoid, it’s still helpful to do some soft tissue release techniques on it regularly to maintain good mobility. This is very helpful before upper body training, especially pull exercises, since the rear delt and surrounding area are prone to getting knotted up; a small amount of soft tissue work will restore mobility and allow you use proper form and to recruit the desired muscles. While you’re at it, I also advise doing a little bit of soft tissue work on the lateral and anterior heads of the deltoid, since these also tend to develop trigger points, which can reduce your shoulder mobility if left unchecked.

- If you have any shoulder or scapular issues, avoid any rear deltoid exercises that cause pain or discomfort, as well as exercises that you can’t get to activate your rear delt. For the longest time, I could not get the dumbbell bent over rear lateral raise to work for me on my left side – Sometimes I’d get discomfort in my shoulder region, but the main problem was really just a lack of posterior deltoid activation. I eventually realized this was due to shoulder instability caused by poor scapular mobility, which I have since addressed. However, before I fixed the root issue, I was able to get a decent posterior deltoid workout by choosing a different exercise – In my case, I had much better luck with the rear delt raise and rear delt row, especially the machine variations.

Hello Alex! I just wanted to give you a big thumbs-up for your good info on the rear delt in this post.

I saw your anatomy articles and they have great info, too. This is an awesome studying resource 🙂

Alex!

I have been battling shoulder impingement/ severe upper back and chest pain on my left side and can’t seem to fix it for about 3 months. There is tingling/pain and tightness in my arm when i stretch the pecs or retract the shoulder blade back and down. I have been trying to stretch the pecs, strengthen the lats and serratus anterior and foam roll. any advice?

Hi Taylor, sorry to hear about those issues. For something so specific and likely nerve-related that’s causing major pain, you definitely need to get a doctor’s opinion.

It sounds like it could be some type of compression of the brachial plexus, which is a group of nerves that comes out the cervical spine, goes through the scalenes, under the collar bone, then under the pec minor, extending into the shoulder blade region and down the arm. A common condition associated with the compression of this nerve is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. What you have may or may not be that. But you may want to look into that to discuss it with your doc.

I hope you recover soon!